The article on this page originally appeared in JSSUS newsletter Volume 48 no.2 2016.

Restoring Armour and Swords – Contrasting Points of View Part D: Koshirae Page 19

Copyright 2018 Japanese Sword Society of the United States

Restoring Armour and Swords – Contrasting Points of View Part D: Koshirae

I. Bottomley, F. A. B. Coutinho, B. Hennick and W. B. Tanner

Whenever collectors / enthusiasts gather, the opportunity to share the enjoyment and passion of their experiences and gathered knowledge is irresistible. The ensuing exchanges are likely to include opinions, examples, vignettes, etc., to the delight of all.

It was, in fact, one such discussion which was the inspiration for the articles published jointly in this series. The discussion revolved around the question of restoration vs. conservation with reference to swords and antiques in general among European and American museum curators and Japanese specialists.

At the outset, the intention was to decide on the superiority of one approach over another as regards armour and swords in general, but as the conversations continued and evolved, it was mutually agreed that the question of the suitable choice of treatment for any piece is as individual as the piece itself. It was determined that a series of articles, focusing on specific elements of armour and swords would be more effective in providing helpful illumination and guidance. These elements have been chosen because they are frequently submitted by collectors for treatment—restoration or conservation.

To date, three articles have been co-authored by Bottomley, Coutinho, Hennick and Tanner. In each of the articles, the nature of restoration vs. conservation is described, as well as the pros and cons of each, as they may be applied to particular parts of armour and swords. In Part A, the focus was on armour; in Part B, the focus was on swords; in Part C, the focus was on shirasaya.

As the series continues with the publication of Part D, the focus narrows a little more, zeroing in on the mounts on a Japanese sword. The term koshirae refers to all of the physical mounting of the sword, excluding the blade itself. For the purposes of this article, three particular elements will be considered: fuchi, kashira and tsuba. It is not unusual to encounter Japanese swords with lost or damaged mounts, but the course of action for the collector with the goal of “improvement” is not always straightforward.

The koshirae under discussion here are located on the handle of a Japanese sword. The tsuba is the sword guard, the fuchi is located next to the tsuba and the kashira is the end cap of the handle.

The koshirae are ornaments for the sword and are often very beautiful, with the result that they are frequently collected separately. In these cases, the collector opts to separate the sword and the koshirae. The sword is put in shirasaya and the koshirae are dismounted and become part of a collection of fuchi-kashira or a collection of tsuba.

The separation of the “parts” of a complete sword is quite common and in accommodating the interest and appetite of koshirae collectors, the value of swords is often compromised. Darcy Brockbank addresses this practice in a recent post on Nihontomessageboard:

“ Some of that we see working out on a daily basis as dealers in Japan actively destroy koshirae to remove the kodogu and put them in boxes. It's because fittings collectors and sword collectors come at this with different perspectives. The fittings collector devalues the sword and the sword collector devalues the fittings. Both groups view it to some degree as a "nice to have" to have the complimentary part there.

The result?

High end koshirae is often empty and high end swords have no koshirae or poor koshirae.

I just saw some fittings that were taken off of a koshirae for a Juyo blade, they were very high end old work. The dealer said, "too good for the sword." A Juyo sword! What he was saying really is if he leaves it together a fittings collector won't buy it at all, and a sword collector will pay for the sword then mentally add about $5k in his head as a buffer in which he will accept the fittings.

The solution is to shred the koshirae, put the fittings in a box, sell them for top dollar to a fittings collector who wants his stuff in boxes, take some other low class fittings that the fittings guy won't buy, put them onto the koshirae to drop its value, return the koshirae to the sword now with low end stuff on it. As a result you max the value of all the items and take advantage of the different perspectives of these two groups. Now you have a 60% return vs. where you were starting out with them together, plus you got rid of some unsaleable junk.

It is... heartbreaking.

And every day it makes any sword that is both a high end sword and has high end koshirae that much more rare. And so more valuable. But it requires a bit of education so that people understand the situation. Not hype.

I have examples now where I can look back and see what has been done to some blades. I see a solid gold two piece high quality Aoi mon habaki ... and then it has a zoo of mismatched low quality fittings. On a black lacquer saya. Well... this probably had something like Yoshioka school menuki, kogai and kozuka that matched the habaki in quality and style... they got ripped off and put in a box, and then all this other stuff mounted up in its place. ”

For the complete discussion of the thread, follow the link below. The quoted section is on page 2. http://www.militaria.co.za/nmb/topic/16234-juyo-shikkake-in-germany/

In cases where koshirae have been kept with a sword--whether they are original or replacements for earlier ones which have been separated for individual collections -- it is not unusual that parts have been lost or damaged. At some point, the collector may be faced with the dilemma: restoration or conservation.

The two examples which follow illustrate the justification for restoration despite the differences in approach.

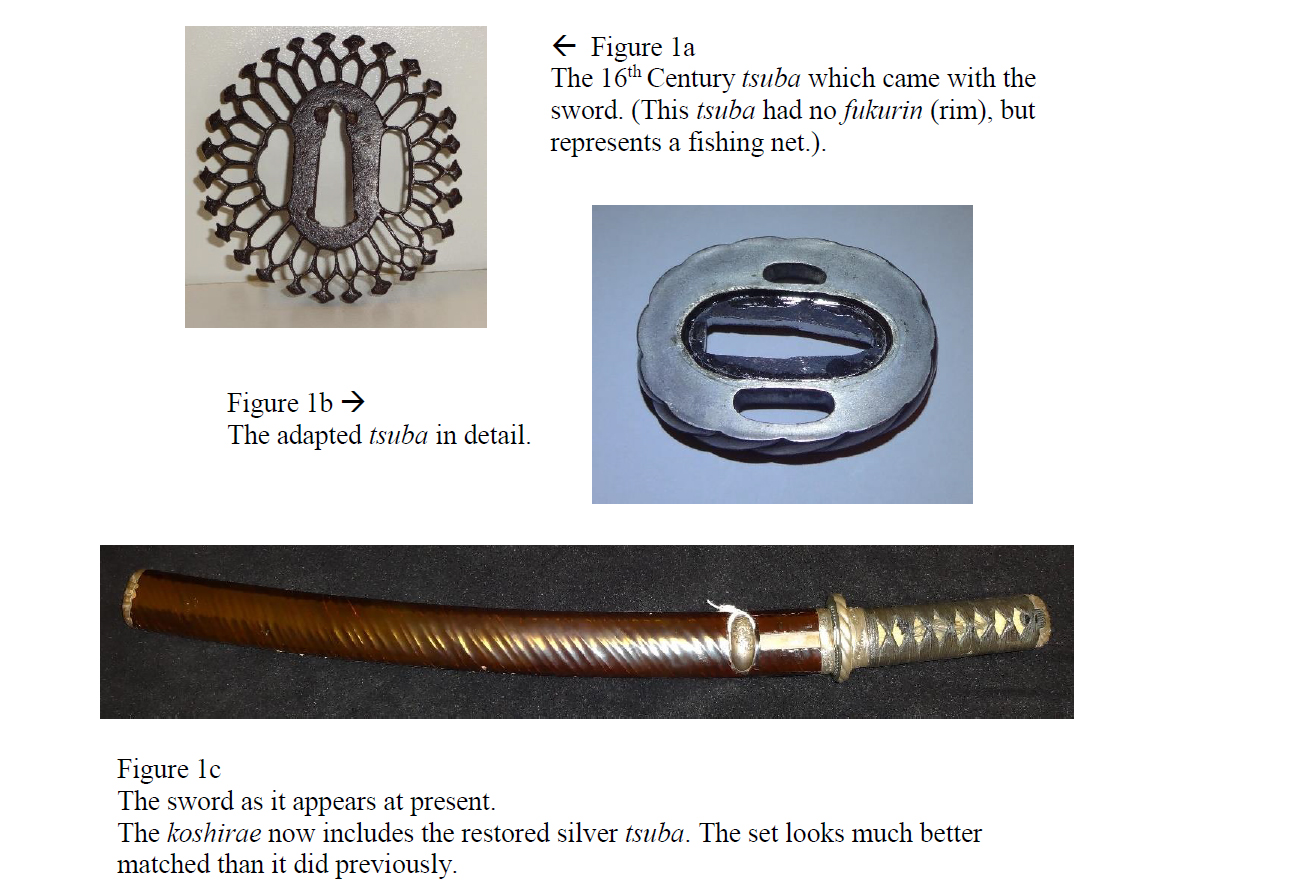

The first case involves a sword which was purchased with koshirae, all of which were present en suite in silver with the exception of the tsuba, which was made of iron; consequently, the tsuba

was not in character with the other parts of the koshirae. In addition, after closer examination, a Japanese expert confirmed that while the koshirae were of the Shinto period (17th Century), the tsuba was 16th Century. Quite by chance a restorer found a Japanese art object using a silver tsuba with a very similar decoration to the rest of the sword’s koshirae. As the design and material of the art object’s tsuba were far more appropriate as part of the sword’s koshirae, the decision was made to use it as a replacement for the iron tsuba which came with the sword.

On removing the silver tsuba, it was discovered that it had been altered so it could be incorporated into the art object; the nakago ana had been enlarged. Only a small adjustment was required; accordingly, with the insertion of a piece of metal (sekigane), the tsuba was adapted to fit the sword. Unfortunately, the art object was changed significantly with the removal of the silver tsuba, but the resulting sword, with its matching koshirae seems to justify this sacrifice.

Figures 1a, 1b and 1c below illustrate the iron tsuba, the silver tsuba and restored sword with the all-silver koshirae, respectively.

The koshirae now includes the restored silver tsuba.

The second case described below involves an excellent sword made by Bungo no Kami Minamoto Masayasu. It was purchased in Japan and came in a handsome Edo era handachi koshirae; all the pieces were en suite except for the tsuba. The sword’s owner chose to show it to a friend who is also a collector and dealer. On seeing the koshirae, the friend became very pale, rushed upstairs and returned with a tsuba he had bought in Argentina many years before. Amazingly, the tsuba was exact match to the koshirae. The friend was a very religious Shintoist and believed that the sword came all the way from Japan to find its tsuba. In the opinion of the owner, however, the koshirae was probably one of a number of duplicate koshirae which had been produced either for some battalion or for sale to foreigners. Most likely, the tsuba came from a koshirae set which had been broken up and ultimately the tsuba ended up in Argentina.

At the beginning of the 20th century, Argentina was the second richest country in the world and even today it is possible to find many Japanese works of art there.

The tsuba shown in Figure 2a is the one included in the original koshirae purchased with the sword by the owner.

The tsuba shown in Figure 2b is the one provided by friend of the owner and “re-united” with the other pieces in the

koshirae.

Figures 2c and 2d show the koshirae as they now appear with the “found” tsuba. Technically this may be described as a case of “de-restoration”. The replacement tsuba seems to fit the overall style better than the one purchased with the original koshirae and no harm was done to the rest of the sword.

Differences in attitudes among collectors with respect to restoration

The recurring theme throughout the series of articles is the different attitudes and approaches with respect to restoration in the sword-collecting community. These differences are most definitely evident when considering the koshirae which accompany a sword.

The general belief in Japan is that a good sword may have more than one koshirae to be used as a mount as befits a specific occasion. Most likely this is true because many sets of fuchi-kashira and matching menuki are readily available for sale in antique stores in Japan; consequently, the easy availability of these items is probably responsible for restoration as a viable choice for Japanese collectors. This situation can be further confirmed by examining any magazine which specializes in Japanese swords.

The current situation among modern-day collectors is quite different from early days of sword use in Japan. Very few samurai could afford to buy koshirae in which all the pieces matched. In fact, many lower-ranking samurai had difficulty buying any kind of sword or fittings and, consequently, had to wear whatever they had inherited or were issued by their lord. The results in these cases were that their swords and fittings were quite eclectic. Unlike the modern Western depiction of the samurai strutting around Edo period Japan wearing a daisho, an examination of old photographs released after Japan was opened to the world reveals quite a different reality.

Many samurai can be seen wearing a disparate pair of katana with a tanto. (A comparison of the incomes of samurai versus the merchant class will be further explored in a future article.)

In contrast, European and American collectors like to have authentic old koshirae in which every piece matches; this type of koshirae is described as “en suite”. In the U.K., as in the rest of Europe, a collector who is confronted by a missing or mismatched kashira is likely to search the market for the necessary piece which matches the rest of the koshirae most closely. This form of restoration conforms to the principles of restoration outlined by Emma Shmucker (Shmucker (2007)) referenced in Part A of this series of articles.

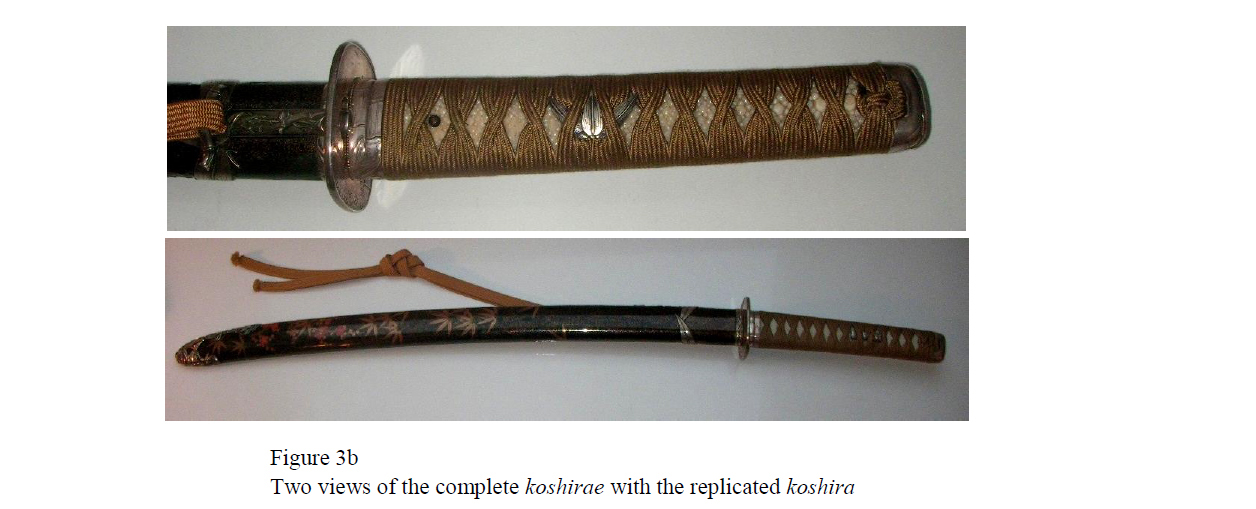

When attempting to find a replacement for missing or damaged part of the koshirae, the collector in the U.S.A. may have more limited resources from which to choose, while still wishing to complement the aesthetic flavour of the koshirae. As a result, some American collectors seek out talented artisans—wherever they may be in the world--who can create an exact replica to replace the missing part. An example of such a replica is shown on its own in Figure 3a and mounted with the koshirae in Figure 3b.

While this form of restoration is widely accepted in Europe and the U.S.A., this solution has not been adopted universally. In view of the disparity of financial resources and regional attitudes, it is to be expected that museums will continue to choose their method of restoration individually, according to the local practice for the foreseeable future.

Restoring a damaged saya

In the previous discussion, the focus was on a lost or missing kashira. When the koshirae are all present but one part is damaged, the options for the collector are somewhat different. The focus of this discussion is the best option for restoring a damaged saya (the scabbard portion of the koshirae) specifically. In most cases, the saya of koshirae is covered with urushi, which is a strong, chemical-resistant, natural lacquer. The versatility of this lacquer allows for a variety of textures, colours and patterns to be applied to the saya, offering the original artisan a wide palette for creation. If the saya cracks or is damaged, however, it may be quite difficult to repair. In Part A, a couple of approaches used in restoring urushi on armour were discussed. For saya, one of the three following approaches is typically used.

Method 1:

The saya is completely refinished in new urushi. Essentially this amounts to creating a new saya, often with spectacular results. This approach is commonly used in Japan, particularly with saya of a single colour. The saya illustrated in Figure 4 has been completely refinished.

Method 2:

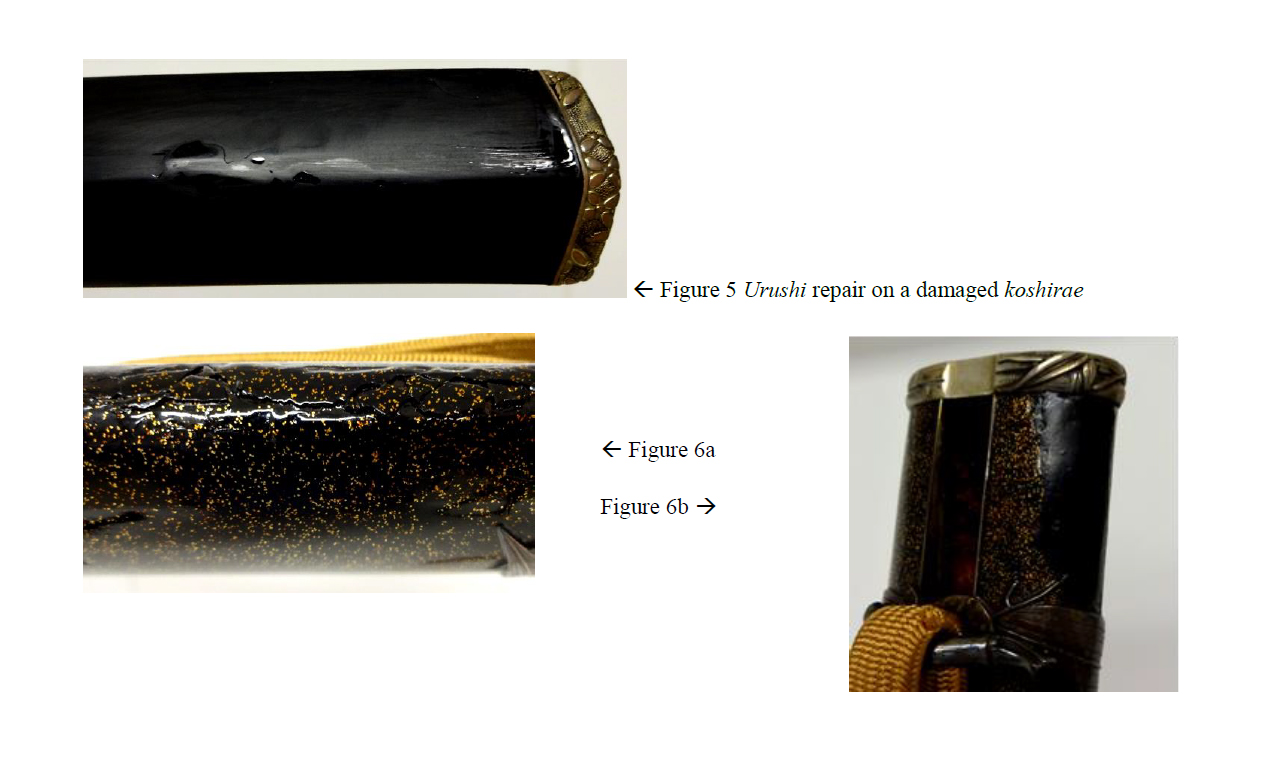

The damaged part of the saya is repaired, after which the saya is refinished in the same lacquer colour as the original. The koshirae shown in Figure 5 is an example of this kind of treatment. A section of the Muromachi era koshirae was gouged and damaged; it was repaired with the original colour urushi. This type of repair does not distract from the original koshirae and would likely be considered acceptable to most Western collectors.

Figure 6a: Clear urushi used to stabilize flaking makie on saya

Figure 6b: Solid-coloured (black) urushi used to repair saya

Method 3:

The damaged area is filled or repaired with clear or solid-coloured urushi. This method has the benefit of using the urushi as a glue to stop further flaking or chipping, as well as preserving the wood in the saya. While this method may not produce the most aesthetically-pleasing result, it does follow the practice of many European conservationists who want to preserve the appearance of the original as much as possible. In many cases, it is the only practical way of repairing a Bakumatsu Era makie saya where the designs and patterns cannot be replicated easily. Both clear and solid-coloured (black) urushi have been used in the repair of the saya shown in Figures 6a and 6b respectively.

When compared to the problems described above, there other issues which may arise on koshirae that might be considered minor. Occasionally, there may be a problem with one part of an otherwise good koshirae; for example, the collector may be faced with a rusty tsuba or one with damaged patina. In such cases, there is a variety of treatments from which the collector may choose:

Do nothing. Leaving the tsuba in its current state allows its condition to attest to its age and history.

Employ “tsuba fussing.” This term refers to a gentle restoration used on an iron tsuba which has red rust. This may involve putting the tsuba in the back pocket of a pair of jeans and walking around with it in the jeans. Over time the cotton denim rubs against the metal and gently removes the rust and polishes the piece.

Use other gentle abrasives. These may be used to scrape away the red rust; three examples are deer antler, ivory or an old copper penny. All three have the advantage of being harder than red rest but softer than black rust.

The following quote from Nihontomessageboard reviews and explores more strategies for dealing with red rust in a gentle manner (http://www.militaria.co.za/nmb/topic/9463-tsuba- restoration/):

“Tsuba fussing" is a great name that is often used for what you want to do. Recommendations that I have heard and seen in practice are:

put the tsuba in your blue jean's pocket and let your walking around etc. gently rub the tsuba.

use ivory pieces to rub the rust off. Whatever you use must be harder than red (bad) rust and softer than black (good) rust.

using choji oil on the rusted area

boil the tsuba in distilled water - dry completely after boiling

put the tsuba in a freezer to freeze the rust off

I RECOMMEND NONE OF THE ABOVE - IF IT IS WORTH RESTORING GIVE IT TO A PROFESSIONAL FOR A PROFESSIONAL RESTORATION.

If it is not worth restoring then sell it and get one that is in such good condition that it does not need restoration or buy one that is worth the restoration and get it professionally restored.”

If none of the methods in the quote above is effective or, alternately, threatens to do further damage to the tsuba, following the final recommendation is likely the best. A trained professional will not only remove the active rust safely but also repatinate the tsuba if necessary. When repatination of soft metals--rather than the iron tsuba referred to earlier—is required, the professional may draw on experience and expertise to accomplish the task more competently.

Frequently the professional is called upon to remedy earlier amateur efforts at restoration; this is often more difficult than starting with the original tsuba. Enlisting the help of the professional is the most reliable way to ensure that, when the work is completed, it will be possible to see the tsuba as the original maker intended.

John Stewart wrote the following on Nihontomessageboard:

“You can be quite sure tsuba are restored. This usually is a matter of repatination. Ford Hallam repatinated a sentoku tsuba for Brian (I believe) that turned out fab, for example. Even removing active rust from iron tsuba and pocket buffing them could be considered restoration, yes? “

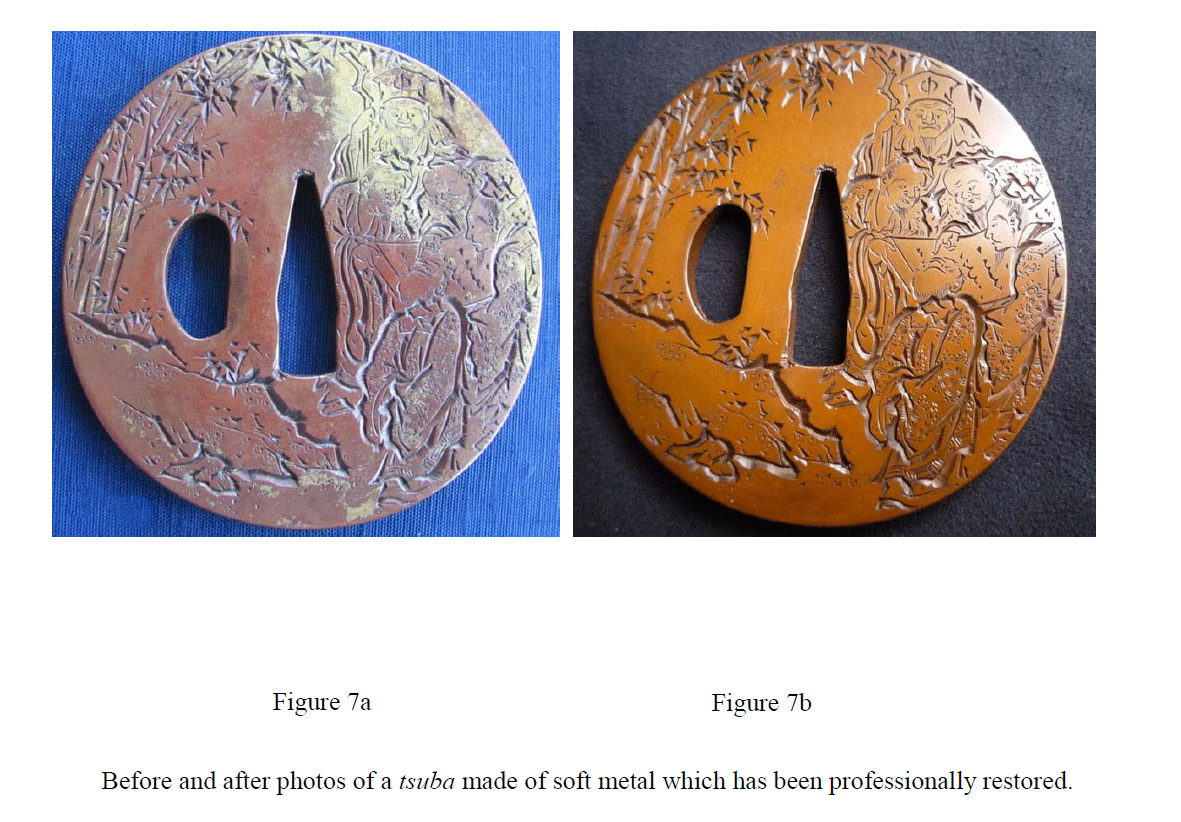

The soft metal tsuba mentioned above is shown below in Figures 7a and 7b, before and after professional restoration, respectively

The owner of the tsuba provided the following description of his interaction with Ford Hallam, the professional who did the restoration. It is clear from his words, quoted below, that he was very satisfied with the result:

“The gold flash coating was determined by Ford to be not original and not part of the design. It is assumed and presumed to be gimei, and not of huge value, but is a wonderful example of a careful and necessary restoration.”

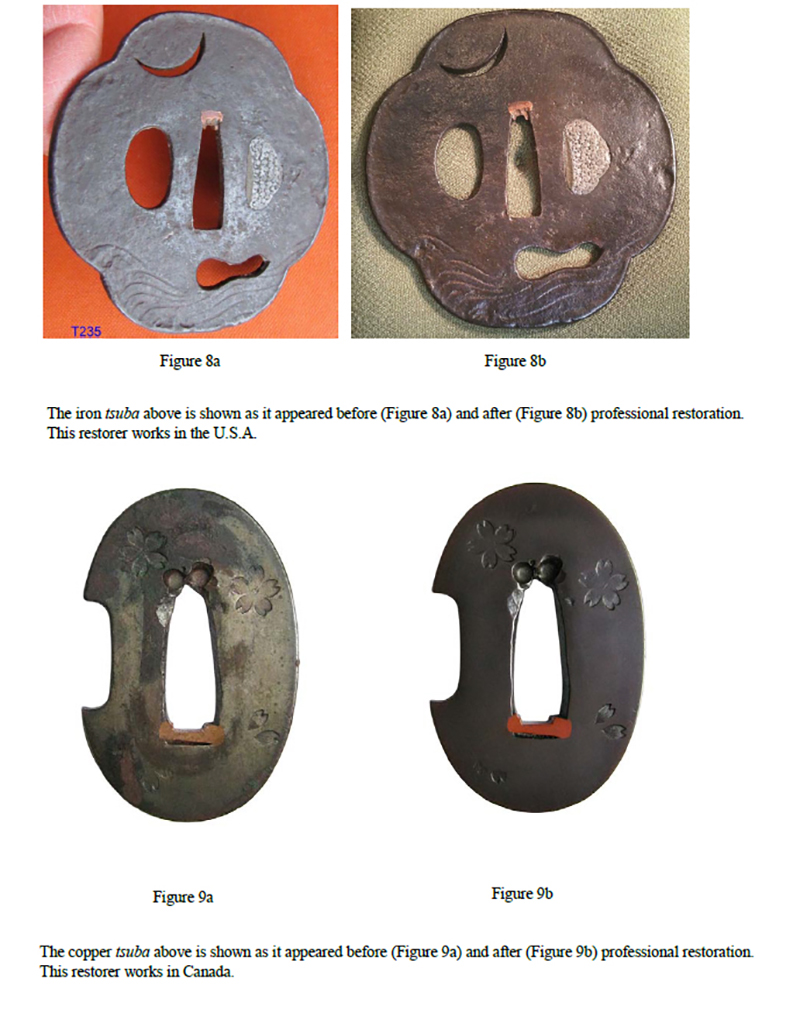

Additional examples of professionally restored tsuba are included below; each set is followed by a brief description.

The following account has been provided by senior collector and traces his earliest experience as a novice collector.

"When I was about 14 I bought a rather mangled sword with mismatched fittings of dreadful quality and a leather combat cover. For some reason this remained in the parental home when I married, being rediscovered in his study on the death of my father. Being now of sentimental value, I decided to restore the blade and mount it in a better koshirae. This was in the days when contact with Japan was for me virtually impossible, and materials such as samé or urushi absolutely unobtainable. I did however manage to acquire a plain wood scabbard from a military combat cover and a military hilt from which I managed to produce a bare wood scabbard and samé covered hilt. Next to be acquired was a set of iron handachi fittings and a pair of menuki, which dictated the style the new koshirae was to be. There remained the problem of how to imitate the lacquer on the scabbard. After playing around with different materials I settled on acrylic resin of the type used with fiber-glass. A couple of coats pigmented with carbon black were put on as a base followed by a clear layer sprinkled with sieved pieces of crushed abalone shell. Two more coats of clear gave the necessary visual ‘depth’ that when sanded smooth and polished produced a finish that has a fair resemblance to urushi. The sword was finally completed by a large tenpo tsuba with later decoration of the kamon of the Date family given me by an old friend. Although it is an absolute fake, it holds memories for me of my parents and a dear departed friend and I wouldn’t alter it for the world."

This description clearly reveals the strong affection he had for the very first Japanese sword he acquired. Each repair and improvement was carried out after considerable research and effort; each well-thought out addition was made with a desire for historical accuracy. This was definitely a labour of love. In spite of his admission that the sword is “an absolute fake”, his emotional connection with it will remain a treasured memory.

The collector’s study of the initial condition of the sword was essential as a forerunner to his attempts to make whatever changes were required to restore the sword to its origins as regards style and era.

When collectors gather, they are unified by their shared passion. When they relate stories of their personal experiences, triumphs and occasional frustrations, they may be confident that they are speaking to an understanding audience. In this exchange, advice and knowledge are often passed through vignettes which carry important lessons.

Discussions of this sort may encompass all aspects of collecting Japanese art objects—armour and weapons included—but since this article has been highlighting fittings, the cases included refer to discussions with collectors of fittings.

The two cases described are based on actual conversations with American collectors of fittings.

Case 1:

One serious fittings collector stated his conclusion that it is almost always a losing proposition. Since he has lost money on every attempt he has made, he has decided not to have any more restoration done. The specific example he provided was as follows. He found a nice tsuba and paid $500 for it; the necessary restoration cost an additional $300. When the work was complete,

he had to pay $250 for papers. Ultimately, he ended up with a disappointing Shoami attribution and sold the tsuba at a big loss.

Case 2:

Another collector put together a Higo koshirae where all the fittings matched. He also made a leather sageo for the koshirae. The sageo looked fine, but no doubt he will lose money when he tries to sell this koshirae.

A common practice among European and American collectors is the attempt to “improve” their koshirae. As the two preceding examples illustrate, they may choose to do this at their own peril and without certainty of a satisfactory outcome. The collector’s motivation in deciding to make this investment is key.

If it has already been established that the koshirae is not original, making a change to satisfy the esthetic preference of the collector might be acceptable, providing that the collector is aware that this may not necessarily increase the monetary value of the final koshirae.

Similarly, regardless of the personal preference of the collector, care must be taken that whatever new tsuba is selected to complete the koshirae, it should at least match the style of the rest of the parts.

At the outset, the collector makes the decision to acquire any new object because it has appeal on some level. Perhaps it is a beautiful example of a favourite era, school or a particular smith. It could be a piece which will complete or enhance an already-existing collection. Whatever the reason for acquiring it, the collector may ultimately face the dilemma of whether or not to proceed with restoration should it be required. Over the course of the four articles, various aspects of issues confronting collectors were explored: examples of the choices made by collectors, the success or failure of the efforts that ensued and the points of view of both scholars and enthusiasts whose only credentials may be their personal experiences and quest for knowledge.

It is a widely-held belief among collectors that they never truly “own” the object(s) of their interest but are privileged “guardians” for a relatively brief part of the journey of the object(s) through time. As such, while they are permitted to enjoy and learn from these objects during their “temporary” relationship, collectors are entrusted with their care and protection.

As mentioned repeatedly throughout Parts A, B, C and D, diverse factors come into play when decisions regarding the restoration of any artifacts. It is important to consider the financial restrictions of the individual collector or organization involved in the decision and whether the planned restoration will put an undue strain on those resources.

the appropriateness of the restoration: Special care must be taken to ensure that whatever alterations are made will match the existing features of the artifact.

whether the artifact merits an elaborate or costly alteration: It may be argued here that the ultimate happiness of the collector justifies whatever changes are sought. The issue is complicated, however, when the financial investment required for the restoration

surpasses the final monetary value of the object, as described in the collector’s experience in case 1 immediately above. If the collector deciding on the restoration chooses the plan with the realization that the main (and possibly only) reward will be personal enjoyment for the duration of the ownership that choice becomes easier to accept.

the goal of the collector or organization in choosing restoration. This is directly related to the point immediately preceding this one. On a purely idealistic level, it would be nice to believe that all restorations are carried out only as attempts to make the objects the most accurate, beautiful and complete they can possibly be. In reality, though, the changes are made not only for aesthetic reasons but to make the artifacts more marketable and worthy of a higher financial return.

While many of the ideas, observations and opinions expressed in this and the foregoing articles may apply to many types of collectables, it is important to recognize the particular elements which exist when discussing Japanese artifacts; these include different attitudes concerning restoration / conservation (both historic and ongoing), examples of choices made by collectors of the two main groups (those in Japan and those outside of Japan—often identified as European and American) and the resultant success or failure of some of these choices.

It is hoped that these articles will provide insights and enrich future experiences for both novice and seasoned collectors alike, and promote continued acquisition and sharing of knowledge. The best reward will be evidence that collectors of Japanese art objects are driven by appreciation of and respect for the artifacts in their care and not purely as investment opportunities or the desire for exploitation.

Acknowledgment

Thanks are offered to Sylvia Hennick our patient, hard-working editor who has taken four separate voices and combined them in to one articulate voice. Her able assistance is greatly appreciated.

References

Bottomley (2015) - Bottomley I., Couthino F. A. B., Hennick B., and Tanner W. B. Restoring armor and swords – contrasting view points Part A – Armour, Newsletter of the Japanese Sword Society of the United States Vol. 47 #3 pages 13 - 24

Bottomley (2015) - Bottomley I., Couthino F. A. B., Hennick B., and Tanner W. B. Restoring armor and swords – contrasting view points Part B – Swords, Newsletter of the Japanese Sword Society of the United States Vol. 47 #4 pages 20 - 36

Bottomley (2015) - Bottomley I., Couthino F. A. B., Hennick B., and Tanner W. B. Restoring armor and swords – contrasting view points Part C – Shirasaya, Newsletter of the Japanese Sword Society of the United States Vol. 47 #6 pages 22 - 26

Darcy Brockbank: http://www.militaria.co.za/nmb/topic/16234-juyo-shikkake-in-germany/ Barry Hennick: http://www.militaria.co.za/nmb/topic/9463-tsuba-restoration/

Schumacker (2007) - Emma Schumacker, The conservation and Display of a Japanese helmet,Arms & Armour 4 (2) 145-158