The articles on this page originally appeared in JSSUS newsletter Volume 50 no.2 2018.

Connoisseur’s Notebook: Chinese Carvers Working In Japan During The Edo Period, Part Two James L. McElhinney - Page 6

Connoisseur’s Notebook: What’s In A Name? How “Chinese” Swordguards Became “barbaric” James L. McElhinney - Page 11

Connoisseur’s Notebook: Sword-guards From Vietnam James L. McElhinney - Page 15

Copyright 2018 Japanese Sword Society of the United States

CONNOISSEUR’S NOTEBOOK

By

James L. McElhinney

© 2017

CHINESE CARVERS WORKING IN JAPAN DURING THE EDO-PERIOD

Part two: Kiyou-Tojin Tsuba

(Reverse)

Large rectangular sword guard. Iron with gold wire inlay, much of it missing due to use. 8.15 x 7.5 x .4 cm. The manner of execution represents a high degree of artistic hybridity, suggesting that this piece was made along maritime trade-routes, where artisans had access to decorative arts from around the globe. The indented corners, pointed Shitogi-gata seppa-dai, smooth-skinned dragons and almost caricature drawing- style points to Indochina, perhaps Tonkin. There is a similar piece in the 1973 W.M. Hawley book Tsubas (sic) in Southern California. I have seen a number of similar pieces with NBTHK attribution to "Nagasaki". At first I was dubious, believing it more likely is that these were imported to Japan through the VOC factory in Deshima. Cultural exchanges between China and Nagasaki became quite frequent after the Kangxi emperor reopened Qing seaports to foreign trade in 1684, and issued trading licenses to private concerns.

(The obverse of the tsuba pictured above)

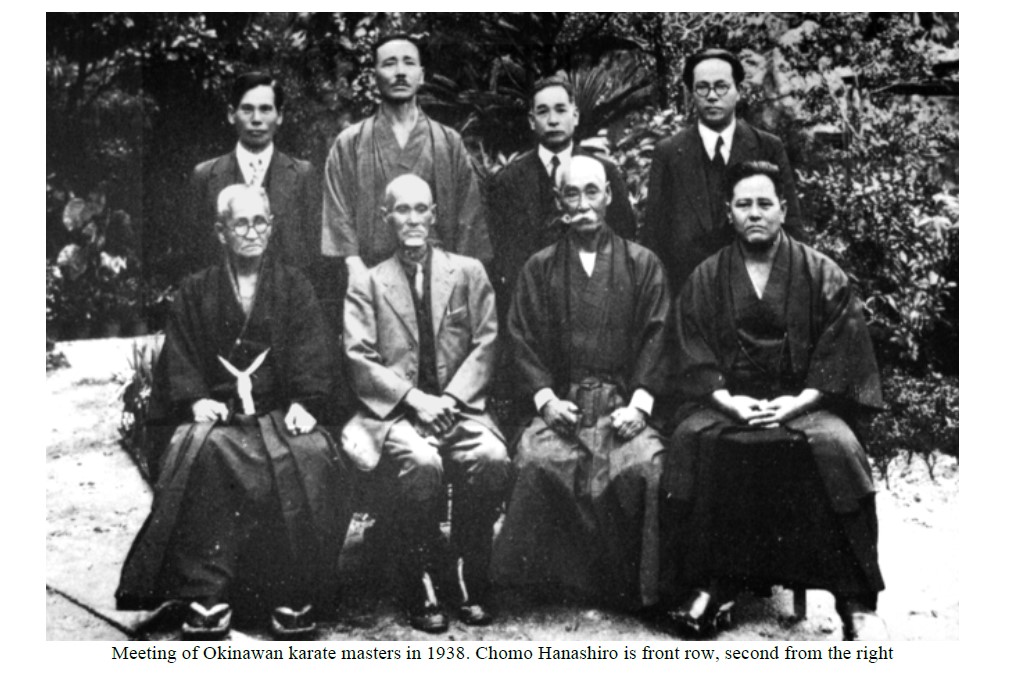

In the 1640s a number of refugees from the collapse of the Ming Dynasty emigrated to Nagasaki. One of them—Shoyu Itsunen became the abbot of Kofukuji temple in Nagasaki. Itsunen is also known to have taught painting to Kawamura Fukuyoshi, a samurai and customs official who is better known as Jakushi I. Another Chinese priest, Yinyuan Lonqi, was the abbot of Wanfu temple on Mount Huangbo in Fujian. He came to Nagasaki at the invitation of Itsunen. Lonqi, known in Japan as Ingen Ryuki, became the founder of Obaku Zen Buddhism. The Nagasaki school of painting was deeply influenced by the Chinese painter Shen Nanpin, who lived and taught painting in Nagasaki for several years. Nanpin’s work was heavily influenced by European scientific and botanical painting, which resonated with the intellectual community at Nagasaki, which in Japan was the center of Chinese medical studies, and Rangaku (the study of European science).

Stylistically identical to the tsuba illustrated above, the piece below is decorated with dragons, phoenix and tiger, carved in low relief and decorated with wire inlay. The carving borrows much from cinnabar lacquerwares, while the wire inlay evokes the bullion embroidery on silk textiles. The rounded cloud-forms are associated with Qianlong period (1735-1796), or later.

The cloverleaf/rice-ball shaped (shitogi-gata) seppa-dai is intentionally eccentric. The guard was never mounted, but preserved as an art-object or curio, reinforcing the theory that guards like this were made to be used as a gift--not necessarily meant to be worn on a weapon. Some, such as the first example above clearly saw use. The ha end of the nakago-ana is flattened, in the Chinese manner, not pointed in the Japanese style. The seal-script has yet to be translated definitively. One nihongo reading might be “Chikamune.” This probably is an art-name. This maker is not listed in Haynes's Index.

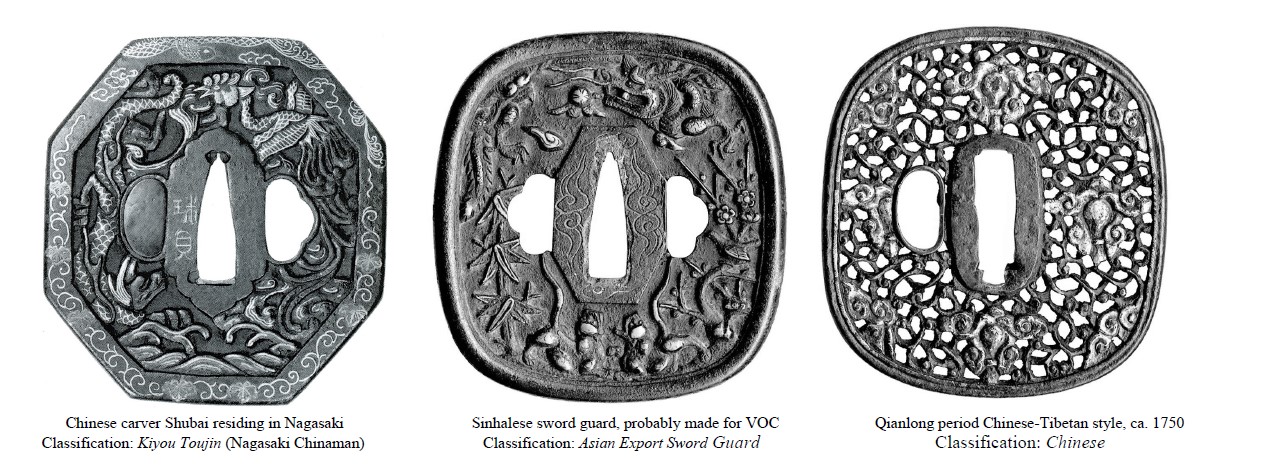

(Private European collection)

A similar example (below) was published in the Token Shibata magazine Rei. The seal-script signature is “Shubai”, listed in Haynes’s Index. H.08805.0 (ca. 1650-1700). Haynes identifies Shubai as an “artist from China”. In his book Nanban Tsuba, Yoshimura Shigeta illustrates a similar piece on page 10. The caption reads, “Nagasaki-he gairaishita Chukokujin no saku…” (Said to be made by a Chinaman who came to Nagasaki). This guard is signed with silver wire inlay. There is little wear, but evidence of Japanese use, as in the presence of copper sekigane and punch-marks around the ha end of the nakago-ana.

|

|

This guard is signed “Shubai”, which can also be read as “Shukai” or “Jubei”. Hedging its bets, the NBTHK issued a Hozon certificate in 2009 that identifies the maker as a resident either of Guangdong Province, China, or Nagasaki, Hizen Province. This is significant because NBTHK acknowledges the possibility that this piece might have been made by a Chinese carver working in Nagasaki. Were this piece unsigned, it would surely have been branded simply as “Nanban”, or perhaps “Nagasaki”.

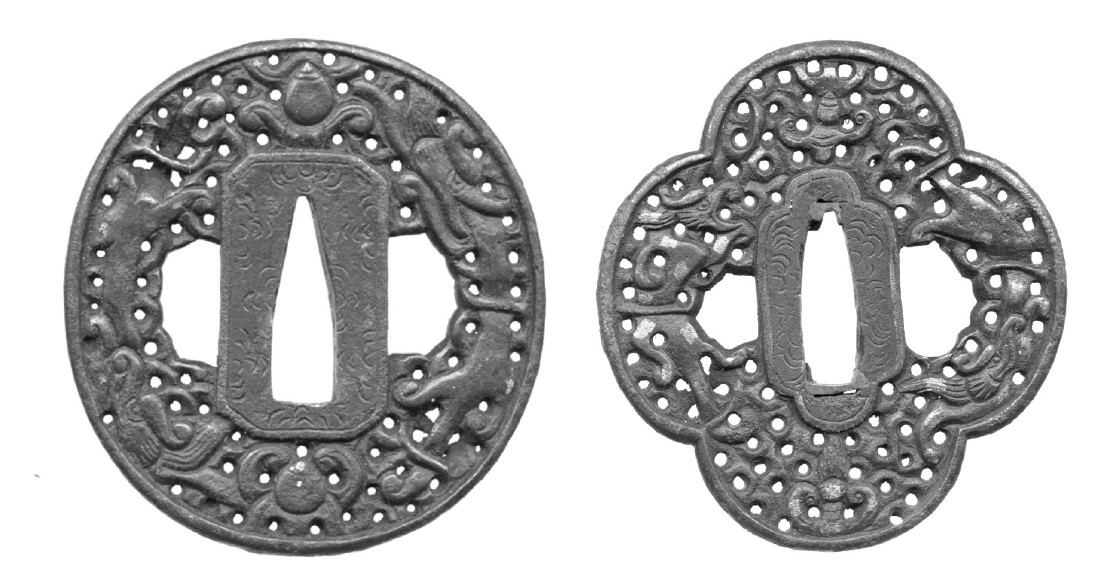

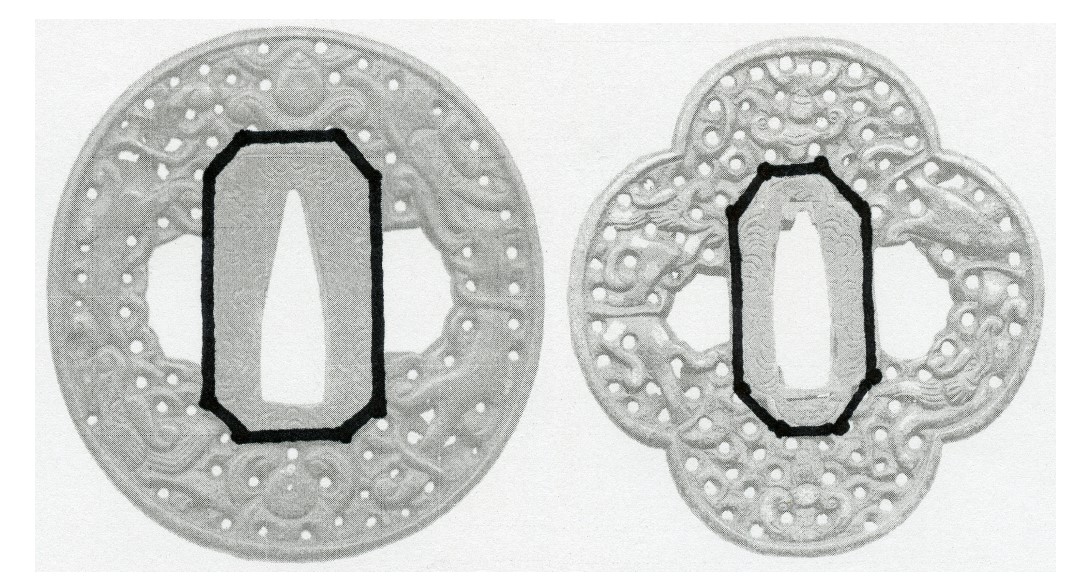

Let’s look at a final example. This iron tsuba is fitted in a box with hakogaki by Kanzan Sato, with an attribution to Nanban. The guard is iron, mokko (quatre-lobed) form. 9.25 x 8.4 x .55 cm. The double rim encloses a dynamic design of dragon and phoenix entwined amidst Loukong/Karakusa interlacing, with three Kiri-ba (Paulownia leaves)—a traditional Japanese symbol associated with the Imperial household

and the national government. Looking at drawing conventions; how the forms are rendered, one finds striking similarities with the preceding examples, together with a number of differences. While the preceding examples are framed by wide wire-inlaid rims, the guard below has a double border enclosing a row of beads or jewels—an archaic motif. While the overall effect is evocative of Qing sword-guards, the style is not purely Chinese, but a novel synthesis of decorative tropes associated with Asian Export art.

"Nanban" tsuba with hakogaki by Dr. Sato. 9.25 x 8.4 x .5 cm. Iron with gold wire inlay, some of which is missing due to use. The author of this guard was probably Chinese, possibly a resident of Nagasaki. Many Asian sword- guards employ histu-ana (bye-knife holes) as purely decorative elements, even plugging them with copper alloys in the Japanese manner. Japanese weapons were highly prized across Asia. Thus, any allusion to Japanese form and style by local arms makers might be seen as an effort to make their products more desirable. For a while Tonkinese weapons-makers reproduced Japanese arms, as evidenced by Admiral Tromp’s weapons-rack in the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam.

The pointed seppa-dai is nearly identical to the Shubai tsuba published in Rei, as is the many of adorning the figures and leaves with gold wire inlay. The peculiar drawing style used to delineate the forms in this guard is the same as that employed in the preceding sword-guards. Given these striking similarities, this final specimen might also be classified as Tojin-Yashiki Tsuba, perhaps the work of a different atelier. We must also consider the possibility that this could have been made in China and imported to Japan. Either way, it no longer is possible to simply dismiss a Chinese-looking sword guards as “Nanban” when the likelihood exists that they were produced by Chinese artists who may have lived and worked in Japan.

Nagasaki’s Tojin-Yashiki grew up around the Chinese cantonment. Its population greatly outnumbered the Dutch. It is widely assumed that the Dutch held a monopoly on foreign trade in Japan. As I have stated in previous articles, Sakoku Japan was far more porous than 20th century revisionist would have us believe. Foreign goods flowed into Japan through Satsuma from the Ryukyus, through Hirado and Tsushima from Joseon (Korea), through Hakodate through Russia and Manchuria. Less attention is paid to the Chinese based in Nagasaki because they conducted business as a community of private merchants, whereas the VOC factory at Dejima was recognized by Edo as the official diplomatic and trade mission of a foreign state.

Even if a debate were to continue about whether some, or all of these guards were produced in Nagasaki, in Guangdong province, Guangzhou city or elsewhere in China, it is more likely that they were imported to Japan by Chinese merchants than by the United Dutch East India Company. The V.O.C seems to have relied more heavily on Sri Lankan and Monsoon Asian suppliers for such goods. Engelbert Kaempfer (1651-1716) wrote that when preparations were underway for an ambassadorial Hofreis trek to Edo, on years when no company ships had arrived from Batavia, the Dutch were forced to buy from the Chinese gifts to be distributed along the way.

As more information is gathered about what used to be known as “Nanban” tsuba, new nomenclature is needed to describe these objects with greater specificity. The four sword-guards discussed in this article share a highly distinctive style. Two of these specimens bear signatures. Based on a comparison of materials, technique, subject and style, it is safe to say that enough similarities exist to identify these works as having been produced by the same atelier, at very least belonging to the same community of carvers. These works have been identified by Yoshimura, Haynes (and cautiously by the NBTHK) as having been produced by Chinese carvers working in Nagasaki. Because Chinese residents of Nagasaki during the Edo period were required to live in a cantonment known as Tojin-Yashiki (Chinatown), these sword-guards might be classified as Tojin- Yashiki Tsuba, or perhaps Kiyou (Nagasaki) Tojin (Chinese) Tsuba.

(To be continued)

CONNOISSEUR’S NOTEBOOK

By

JAMES LANCEL McELHINNEY

© 2017

WHAT’S IN A NAME?

HOW “CHINESE” SWORDGUARDS BECAME “BARBARIC”

Captain Francis Brinkley was one of those rare westerners, Like William Adams, who found a place in Japan’s closed society, close to those in power. Adams had born in Gillingham in Kent, downriver from the Deptford shipyards on the Thames below London. Serving Tokugawa Ieyasu as hatamoto, or standard-bearer. Adams is alleged to have poisoned Ieyasu against the Catholic Spanish and Portuguese, and opened the door to the Protestant British and Dutch. Born in County Meath in 1841, Francis Brinkley was a member of the Anglo-Irish gentry who, as an officer in the Royal Artillery, was assigned to the British Embassy. He married into the samurai elite, resigned his commission and became a close adviser to the Meiji government. Brinkley simultaneously embarked on careers as a journalist and publisher, which brought him international renown. The Meiji emperor bestowed upon him the Order of the Sacred Treasure, for his service in foreign relations. Since his arrival in Japan in 1866, Brinkley’s keen interest in Asian arts and literature had led him to gather information about the subject, much of it unknown to western readers. In 1901 Brinkley published his encyclopedic Japan and China: Their History Arts and Literature, published by J.B. Millet & Company. Boston and Tokyo.Several chapters are devoted to Japanese sword-furniture. Discussing the Chinese influence on sword fittings, Brinkley classifies some as “Kwan-to” (Kanton/Guangzhou) 広州 or “Kannan” 唐南 (South China). He throws laurels at the Jakushi school and dismisses what he terms “the willow style” practiced by the carvers of Hikone. Nowhere does Brinkley refer to any of these specimens as “Namban”, nor does he use the word in relation to sword fittings. Perusing late 19th century sources I found “Kanton” and “Kannan”, but not “Namban”, except to denote artworks produced in a European style, during the century of Iberian influence

|

|

|

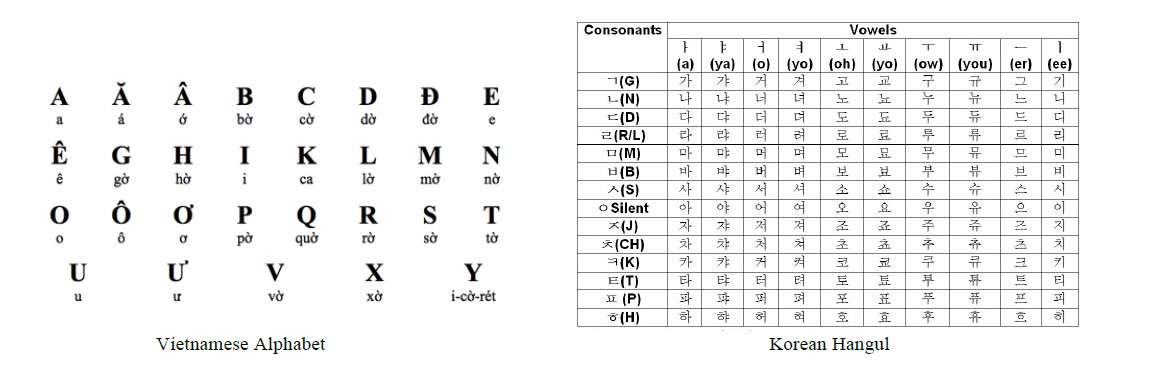

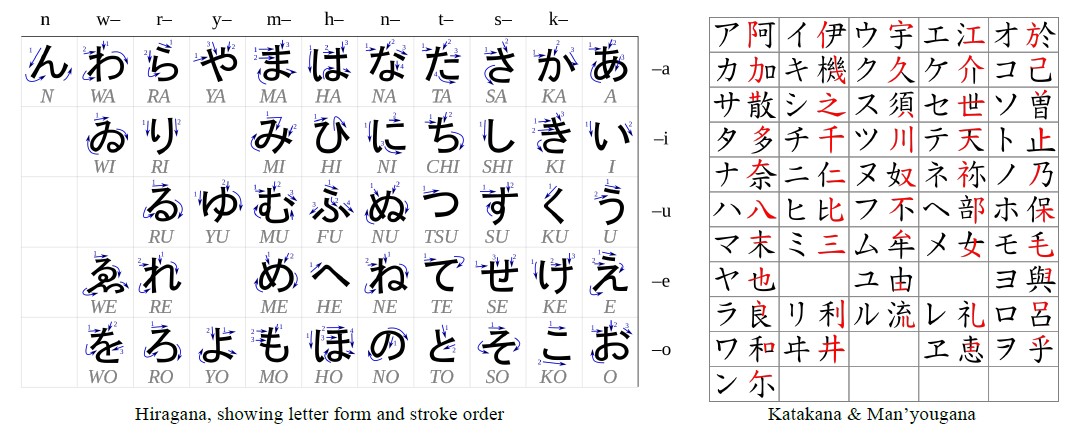

In a paper delivered to The Japan Society on May 14, 1931, British spymaster C.R. Boxer identified discrepancies in the use of the term “Namban” (南蛮) in relation to Chinese-style sword guards. Most of these objects (Kanton and Kannan guards) were made to the taste of the Qing Dynasty (1644-1912). Boxer writes, "The most general term is Namban 南 蛮,literally “Southern Barbarian,” a name applied by the Chinese (in the form Nam-man) to the first Portuguese explorers who visited Canton about 1513, and subsequently borrowed by the Japanese to describe the Lusitanians…. "Later on, this term [Namban] took on a wider significance as was used to include tsuba showing purely Chinese influence (the so-called Kanto or Kagonami [Kannan] tsuba already referred to, as well as those of Dutch origin, which would be better termed Komo 紅毛 “Red Hair”, the common name for Hollanders during the Tokugawa period…As suggested above, the most logical way would be to limit the term Namban tsuba to those tsuba made under the period of Portuguese influence (1542-1639) whilst those on which Chinese influence predominates would be called Canton tsuba, and those deriving from Dutch styles or designs would be termed Komo.”Most of these sword guards were imported to Japan during the middle Edo period, when Japan’s official foreign trade was delegated to the Dutch. Research has revealed that many sword guards known as Kanton (Guangzhou) or Kannan (South China) were inspired by Tibetan and Central Asian saddle-plates, reflecting the official taste of the Qing (Manchu) military of the Qianlong period (1735-1796). These dates agree with the theory that sword guards were imported to Japan from China mostly after 1684, when the Kangxi emperor reopened Chinese ports to foreign trade. As Boxer has indicated, the Portuguese had already departed the scene, which begs the question: how in 1900-1910 does something Chinese magically become barbaric? During theEdo period China was known simply as Kara 唐 (Tang). The Chinese were known as Toujin 唐人 (Kara people, or “foreigners”). In the 19th century (Kara) 唐 became Chukoku 中国 (Central Country, or China) and Toujin became Chugokujin 中国人 (Literally “Chinamen”). Following the First Sino-Japanese War of 1895 and the Boxer Rebellion of 1900, anti-Chinese sentiment became intense. As the Qing government crumbled, Japan, Korea and Vietnam independently took steps to distance themselves from China which had dominated East Asia from antiquity. Cultural cleansing was pursued through changes in language and names. Apt comparisons might include sauerkraut dubbed “victory cabbage” by the Allies in The Great War, or pommes-frites rebranded as “freedom fries” during the second Gulf War. To reduce the dependence on Chinese characters, phonetic non-Chinese writing systems were promoted. Vietnam, by then a French colony, adopted the Roman alphabet, with modifications.

Korea promoted the use of “Hangul”, the indigenous non-Chinese alphabet traditionally used by women, children and the lower class. In 1900, Japan standardized and promoted the use of “Kana”, its non-Chinese writing system, which like Hangul had been associated with women, and people of inferior status. The Japanese language has four writing systems: Kanji (Chinese writing), Hiragana (phonetic Japanese), Katakana (an angular script used for writing Ainu and foreign words) and Man’yougana, the ancient script from which both hiragana and katakana derived.

Prior to these changes, Chinese characters had been the default writing system for poetry, scholarly writing, and official documents. Apart from diminishing the use of Chinese characters, the shift to phonetic writing systems greatly expanded the readership of newspapers, periodicals and books, to include less educated members of society. This led to the development of Western- style news media, if not always a free press.

European writers like Henri Joly, and Japanese expatriates Okabe Kakuya popularized the term. This appears to explain how Chinese sword guards came to be classified as barbaric (Nanban).

For over a century the word hovered like fog above these mysterious objects, which were scorned and neglected by the Japanese sword-collecting establishment. However, new research has discovered ways of discerning and dating Chinese and Korean guards. Chinese carvers working in Nagasaki produced tsuba in a distinctive and recognizable style that now can be declared a “school”. New species of discoid sword guards have been identified, including sword guards made for the Dutch in Sri Lanka, Monsoon Asia and Vietnam.

In light of these discoveries, continued use of the xenophobic term “Nanban” perpetuates nativist fairy-tales concocted by Japanese fascists a century ago. One hopes that if western connoisseurs can amuse themselves by deciphering these objects, then serious Japanese scholars should be able to do better.

(To be continued)

CONNOISSEUR’S NOTEBOOK

James Lancel McElhinney © 2018

SWORD-GUARDS FROM VIETNAM

Discovering new data about what Japanese nomenclature has termed Nanban tsuba has required this outmoded classification to be dismantled, and reorganized into new categories. Applying Linnaean methods to these objects—the comparison of visible traits both within known species, and against objects of similar form, materials, techniques and decorative schema—new subspecies have emerged. Written sources state that Nanban tsuba are sword-guards produced in China and India, which were imported to Japan, and copies of these sword-guards by Japanese metalworkers. These imports were known by many names in China, Korea, Monsoon Asia and India. In none of those places did their makers know them as Nanban. Certifying agencies today should take note of the differences between imported foreign guards, and Japanese tsuba produced in a foreign style.

During the early modern period (roughly 1500-1800 CE) the regions collectively known today as the Socialist Republic of Vietnam was heavily engaged in maritime trade. From antiquity, the regions of Tonkin, Annam and Cochin-China had intermittently been governed by China. For most of their history, these regions were frequently engaged in conflicts between ruling cliques and were often at war with their neighbors. When the Ming imposed a series of exclusionary edicts known as Haijin, or sea-bans, Chinese merchant mariners established trading factories along trade routes traversing Monsoon Asia, including what today is Vietnam. Over the centuries, these Chinese settlements developed into thriving expatriate communities, like today’s Chinatowns.

Indochina provided a market for many of the edged weapons exported from Japan during the Muromachi period. Local armorers borrowed design concepts from these imports, such as curved blades with longitudinal ridges and discoid hand-guards. Japanese forms were thus adapted to local taste. Vietnam in particular is known for having produced facsimiles of Japanese edged weapons, as may be seen today on Admiral Tromp’s weapons-rack at the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam (below).

Tonkinese (northern Vietnamese) metalworkers also gained distinction by producing Sawasa; black and gold decorative objects, including sword-fittings, made by gilding fire-lacquered bronze. For a time, Sawasa sword fittings were imported to Japan by the Dutch East India Company, along with blades made in Solingen, to be assembled by Japanese craftsmen into military hangers and hunting-swords for the European market. Tonkin wares were soon supplanted by Sawasa-style fittings produced in shakudo and gold by Japanese carvers. Admiral Tromp’s weapons-rack demonstrates how Vietnamese arms manufacturers produced weapons patterned after Japanese and European prototypes. Swords made for the domestic market also included edged weapons of Chinese and Monsoon Asian form, such as variations on the peidao and dha, respectively. The peidao (Chinese saber) was equipped with a discoid or cup-shaped hand-guard (Hushou), while the dha (Thai/Burmese saber) might or might not have been fitted with a hand-guard, at the discretion of the maker, or of his client.

One of my previous articles recounted the interactions between the Dutch and King Pye of Burma. The Dutch are known to have purchased weapons along maritime trade-routes, for use as business and diplomatic gifts. Among those gifts were sword-guards, such as those received from Isaac Titsingh by Hirado Daimyo Matsuura Kiyoshi in 1780. Two plus two still equals four. As the Dutch were buying weapons and sword-fittings from Vietnam, and as Vietnamese swords produced for the local market were equipped with discoid hand-guards, it is logical to deduce that sword-guards were amongst the weapons and other gift-goods purchased by the Dutch in Vietnam.

The Weapons-Rack of Admiral Cornelis Tromp (1629-1691). Rjksmuseum, Amsterdam, The Netherlands. The edged weapons were produced in Tonkin (northern Vietnam) between 1650-1579. They were given to Tromp in Batavia (Jakarta) in 1680. The wooden rack is Indonesian. The pistols are European. The swords and polearms at a distance are easily mistaken for Japanese edged weapons. This assortment of weaponry demonstrates a high regard for Japanese swords. As goes the old saying, imitation is the sincerest form of flattery.

Getting a Grip

Asian saber-forms can be identified in part by the handles with which they were equipped. Typical cross-sections of Japanese and Korean sword-handles are oval. Chinese handles are rectangular, with right-angle corners, sometimes tapering slightly to the side aligned with the edge. In 1748 the Qianlong emperor, mourning the loss of a beloved concubine, ordered the rectangular sword-handles of his imperial guard to be replaced by ones with rounded corners. The long handle of the Burmese and Thai dha is circular in cross-section.

Vietnamese sword-handles are varied in form, based in part on quarrelsome divisions within the region, and the fact that Vietnamese armorers borrowed from a variety of weapons-making traditions. Despite this hybridity of style, sword-handles of octagonal section seem to have been most common.

Close-up of a dha handle and guard. Burma, Yunnan or Northern Vietnam. If one found the guard detached from its mounting, one might assume it was Ko-Kinko. Note the nanako-like stippling on the surface. Perhaps guards like this were modeled directly from Japanese imports. (www.mandarinmansion.com)

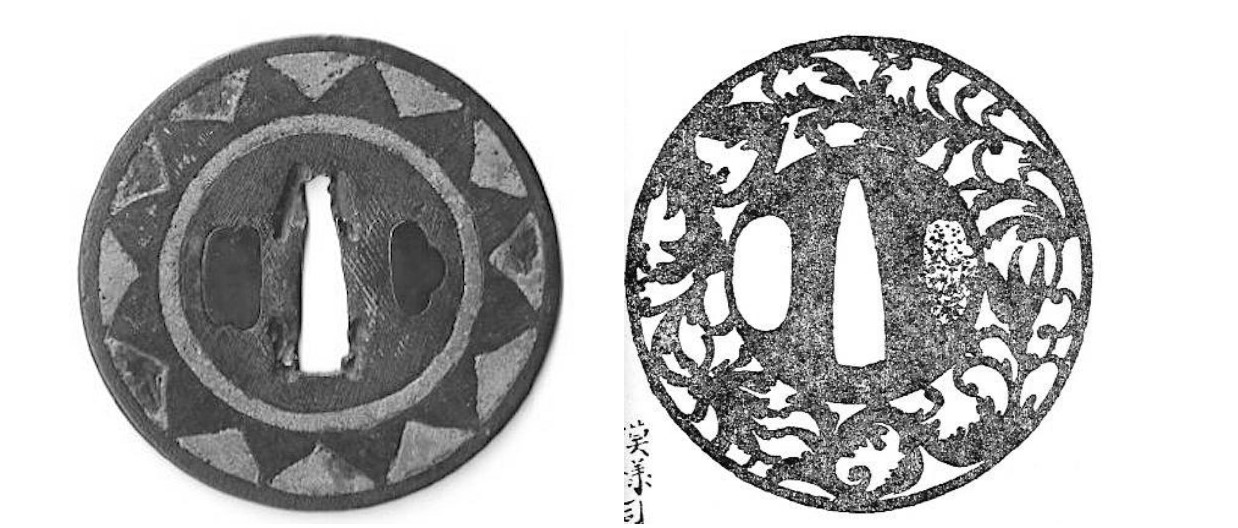

(Left) We may deduce from the circular delineation of the washer-seat (seppa-dai) that this mysterious champlevé guard was made for a round-handled dha, as was perhaps the guard given to Matsuura Kiyoshi in 1780 by Dejima Opperhoofd Isaac Titsingh. (Rubbing (oshigata) courtesy Matsuura Museum, Hirado, Japan.) Identifying probable geographic origins of individual Nanban tsuba can seldom rely on signatures by known makers. Nowhere in Asia, outside of Japan, was it common practice for sword or fittings-makers to sign their work. Because of this, we must rely on the Linnaean method of identifying species by comparing visible traits of form, material, technique and decoration. The first place to address form is the washer-seat, known in Japan as seppa- dai. As we know that the shape of the washer-seat corresponds to the cross-section of the handle, and as we can identify a sword-handle by region, based on the shape of its cross-section, we can thus identify the probable geographic origin of a sword-guard by the shape of the washer-seat. An octagonal washer-seat might be a strong indicator that an Asian sword-guard was made in Vietnam. There are exceptions to the rule, such as two verified Vietnamese sword-guards seen below.

The specimen on the left would have been mounted on a heavy indigenous single-edged blade, while the specimen to the right might be identified in Japan as Ko-Kinko or Kagamishi (mirror-maker) (www.mandarinmansion.com). Both copper alloy.

Two Sino-Tibetan-style “Kanton” guards. The Loukong interlacing is simulated with drilling. Note the surface carving on the octagonal washer-seat on the left. Also, smooth-skinned footless dragons with pointed forelocks express a regional sensibility.

Note the basic octagonal profile of the washer-seat (Seppa-dai). Vietnamese swords were produced with a variety of sword-handle designs, but handles of octagonal cross-section are said to have been the most identifiable

Note the octagonal washer-seat on the left. The design is modeled after classic early Qing guards like the one on the right (ca. 1600-1650). Note its downward tapering rectangular washer-seat, and openwork radiate rim.

Early Vietnamese/Southern Chinese guard in Ming style. Note the octagonal delineation of the washer-seat area, and the rectangular shape of the tang-aperture. The hitsu-ana appears to have been added later. The subject of a cloud-dragon decorates the recto (omote), while five auspicious objects adorn the verso (ura). The rendering of the imagery is bold and somewhat primitive. The different elements seem to be disconnected, almost like clip-art, struggling to strike some balance between the different elements and the negative space around them. (www.mandarinmansion.com)

Early Vietnamese/Southern Chinese guard in Ming style. Note the octagonal delineation of the washer-seat area. The subject of foliate designs appears on the recto, while four auspicious objects decorate the verso. Like the preceding example, the rendering of the imagery is bold. In this piece, the execution is more elegant. The guard retains a coat of green lacquer. Tonkinese metalworkers were known to have excelled at a kind of durable, fire-lacquered bronze in the production of Sawasa wares. Like the preceding example, the different elements seem like disconnected clip-art, lacking the refined sense of negative space one finds on Chinese- made examples, such as the guard seen below.

Note the tapering rectangular delineation of the tang-aperture, executed in silver inlay. The design has a sense of balance and finesse, with a more elegant play between the silver flowers and the negative spaces that surround them. The composition has a sense of motion, as if the elements are turning. The dragons seem animated and mobile. The floral motif appears to have been inspired by textile designs, while the waves resemble work found on Korean sheet-iron boxes and Chinese brush-pots (below).

Above: Kanton (Qing Sino-Tibetan style) sword guard produced in Monsoon Asia, probably Tonkin. This guard replicates the popular subject of the 100-year old carp passing the falls at the Dragon-Gate on the Yellow River in Hunan, to be transformed into a dragon. The design represented personal achievement, like passing the difficult civil service examination, completion of Rangaku training, or graduation from university. This design conflates a civilian motif with an imperial symbol worn by the military, in the form of paired dragons chasing a flaming jewel. Note the serpentine morphology of the dragons, the Loukong interlacing produced by drilling, heating, and bending the metal. An Indochinese design trope is the teardrop-shaped ciliated tama (jewel) and the octagonal shape of the washer-seat (seppa-dai). A closing thought. Nanban (Southern barbarian) was originally a pejorative term devised by the Chinese to belittle the Vietnamese. Ironically, sword-guards made in Vietnam may in fact be the only true Nanban tsuba.

More information is available at: https://www.facebook.com/Asian-Export-sword-guards-and-Nanban-tsuba-564035753684007/