The articles on this page originally appeared in JSSUS newsletter Volume 50 no.1 2018.

Connoisseur’s Notebook: Chinese Carvers Working In Japan During The Edo Perio, Part One James L. Mcelhinney - Page 6

Kanesada Tsuba (金定鐔) David Stiles - Page 10

Real Life Kantei Of Swords 15: Is It Japanese? F. A. B. Coutinho And W.b. Tanner - Page 15

Connoisseur’s Notebook: Kiyou Toujin Tsuba James Lancel Mcelhinney - Page 22

Copyright 2018 Japanese Sword Society of the United States

CONNOISSEUR’S NOTEBOOK

By

James L. McElhinney © 2017

CHINESE CARVERS WORKING IN JAPAN DURING THE EDO PERIOD: Part One

DIMENSIONS: H:70 cm W:67cm T:5mm

MATERIAL: Well-forged carved iron, inlaid and applied with gold highlights

FORM: Naga-marugata, maru-mimi worked to resemble worm-eaten wood or paper, Ryo-hitsu. Minimal tagane and the absence of seki- gane around the nakago suggests that this piece may have been incorporated into a koshirae once, but not multiple times.

DECORATION: Nanga Sansui landscape,

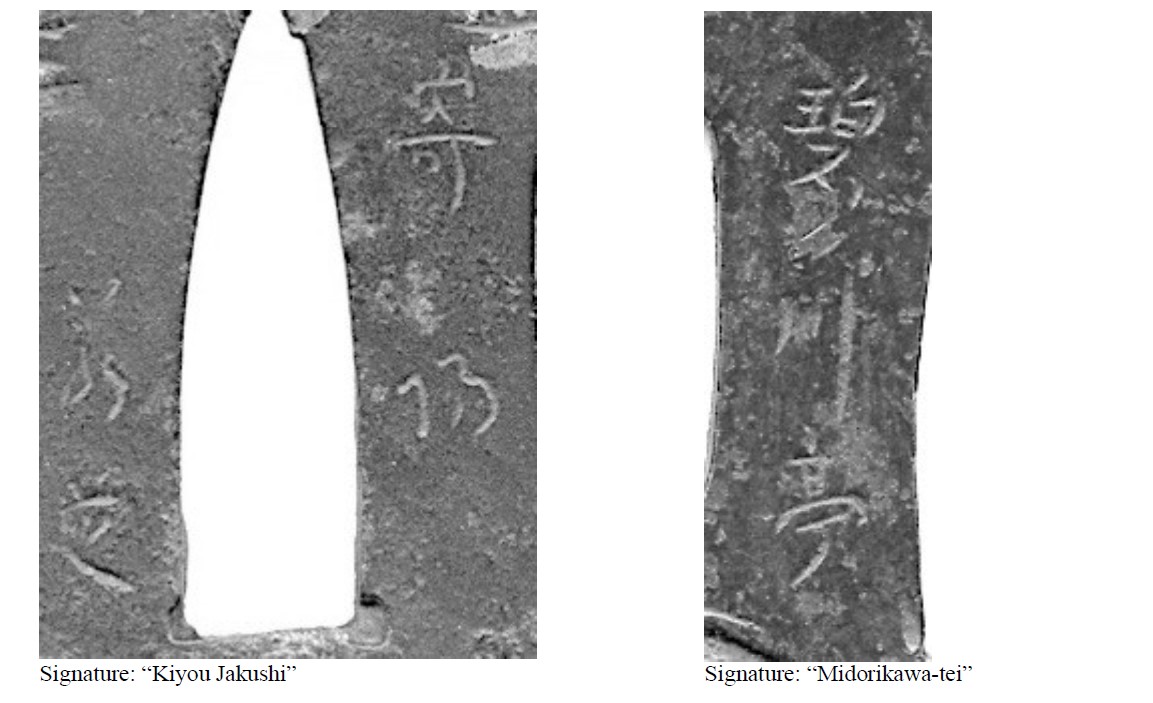

SIGNATURE: “Midorikawa Tei” OR “Midori Sentei”. Collection registration number “941” painted inside nakago-ana in white enamel. Ref. Haynes Index page 1039. Hawley, Tsubas in Southern California, page 877. Provenance: Ex-Craig collection.

CONDITION: Excellent. A thin coat of lacquer that probably dates back to when it was in an unknown museum or private collection. It could be professionally removed, but it in no way should be regarded as damage. Nor does it detract from the artistic value.

NOTES ON THE OBJECT

The subject of the design is a Ming-Qing Nanga landscape. One noted aficionado commented that this piece looks like a sampler displaying many different carving and metalworking techniques. The piece was acquired by the present owner from an American sword collector as “2nd generation Jakushi”, which is most definitely is not. This piece appears as number 877 in W.M. Hawley’s publication of the Nanka Token Kai Tsubas in Southern California under the category of “Chinese Landscapes”. In the book, it was credited to the Craig collection. This is said to have once been in the collection of Robert Haynes.

The decoration of this tsuba is based on the precepts of Chinese Nanga (Southern-picture) landscape painting found in The Mustard Seed Garden Manual of Painting published in 1679, and again in 1701. The book was based on the teachings of late Ming painter Li-Liufang. It was reprinted in Japan and was very influential in transmitting Nanga principles to Japanese artists.

Obaku Zen Buddhism had been established by Yinyuan Longqi, aka Ingen Ryuki, who arrived in Nagasaki in 1654. Yinyuan was an accomplished calligrapher who inscribed paintings by Kawamura Jakushi, Watanabe Shuseki, and others. On land given to him by Tokugawa Ietsuna, Yinyuan (Ingen) established Manpuku-ji temple on Mt. Obaku in Uji. The new Zen sect grew rapidly, due to its inclusion of aspects of Pure Land Buddhism, which enjoyed broader appeal among common folk. It may have contributed also to the popularity of Sencha (steeped tea), and to the appreciation of Chinese art,

culture and medicine. This sword- guard expresses Nanga aesthetics. An entry in Haynes Index of Japanese Sword Fittings Makers and Associated Artists, page 1039, identifies the signature as a family name, Midorkawa, or Aoigawa (green river). The last kanji “Tei” like “ken” is sometimes used as a suffix/particle in art-names. Elsewhere in Haynes’s Index, we find three artists associated with the Midorikawa-kei: Asa, Don and Suisai, who are said have been Chinese carvers working in Japan. No mention is made of their place of residence. The most likely place would have been Nagasaki’s Tojin Yashiki or Chinatown, literally “Chinaman Palace”, or “Chinese Emporium”. During the Edo period the Chinese population rose to nearly five thousand individuals. Permanent residents perhaps constituted half that number, while the number of Dutchmen living on Dejima never exceeded about a dozen.

HOMAGE OR KNOCKOFF?

There is another swordguard of nearly identical form, size, style, and workmanship, signed Kiyou Jakushi. There is no way on God’s green earth that this tsuba was made by the Jakushi atelier. While sansui landscapes were a part of the Jakushi repertoire, the composition feels too cramped, lacking a spacious feeling. The metal surface is too hard, lacking in texture. Jakushi artists used acid-etching to achieve different textural effects on iron surfaces. The nunome is applied in the manner of Jakushi but with less finesse. Finally, the signature resembles nothing like the flourish of a Jakushi-mei. Instead it bears some resemblance to the Midorikawa tsuba described above, in the manner of forming kanji. The two pieces could almost have been signed by the same hand.

DIMENSIONS: H:70 cm W:67cm T:5mm

MATERIAL: Well-forged carved iron, inlaid and applied with gold highlights. Ryo-hitsu with the kozuka-ana filled with shakudo

FORM: Naga-marugata, maru-mimi worked to resemble worm-eaten wood or paper, Ryo-hitsu. Minimal tagane and the absence of seki- gane around the nakago suggests that this piece may have been incorporated into a koshirae once, but not multiple times.

DECORATION: Nanga Sansui landscape, SIGNATURE: “Kiyou Jakushi” CONDITION: Fine.

The question is whether this piece should be considered a gimei (intentional forgery) or an homage of some kind. Kiyou is the Chinese name for Nagasaki. We know that Kawamura Fukuyoshi, aka Jakushi (Young Turf) studied painting under Shoyu Itsunen, the abbot of Kofuku-ji temple in Nagasaki. Itsunen had been born in China, and had studied Linji Chan (Zen) Buddhism under Yinyuan Lonqui, the abbot of Wanfu Temple at Mount Huangbo, in Fujian.

After his arrival in Nagasaki, Yinyuan and Jakushi I collaborated on several paintings, as calligrapher and picture-maker.

The Jakushi masters are known to have signed “Kiyou Sanjin” (Nagasaki Hermit), a nickname adopted by Jakushi I when he retired from his career as a customs-official to become a monk. Translated literally Sanjin means “mountain man”. The use of Kiyou in this context suggests a close affiliation between shodai Jakushi and the Chinese community in Nagasaki. If they were indeed Chinese immigrants, it is possible that the Midorikawa carvers might not have considered copying

Kawamura Fukuyoshi designs acts of plagiarism. That is, after all, what the Jakushi atelier did for nearly two hundred years. The piece being signed simply “Kiyou Jakushi” may be an attempt to draw a distinction between Nagasaki Jakushi and a newcomer calling himself Chinatown Jakushi. It would not be the first time two artists used similar names. The very fact that the maker of this guard has made no attempt to imitate a Jakushi signature questions the notion that this piece was an intentional fake, and suggests that it may have been more of an homage. As usual, more study is required.

Kanesada Tsuba (金定鐔)

by David Stiles

Introduction

In this short article I would like to introduce and discuss the details of a fine Japanese sword handguard (tsuba 鐔) from my collection, which is both interesting and controversial with differing appraisal results. I will present Japanese names, places, and terms, first in italics, followed by the (kanji 漢字) or (kana 名) in brackets to aid the reader in understanding Japanese texts and notes.

Reference to the same term later in the text will only be italicized. The following is a listing of basic information about the tsuba as well as images of the front and back. Color images of the tsuba can be found on my website at the following URL: (https://www.tsubaotaku.com/tsuba-gallery-5? lightbox=dataItem-iifyb2s1).

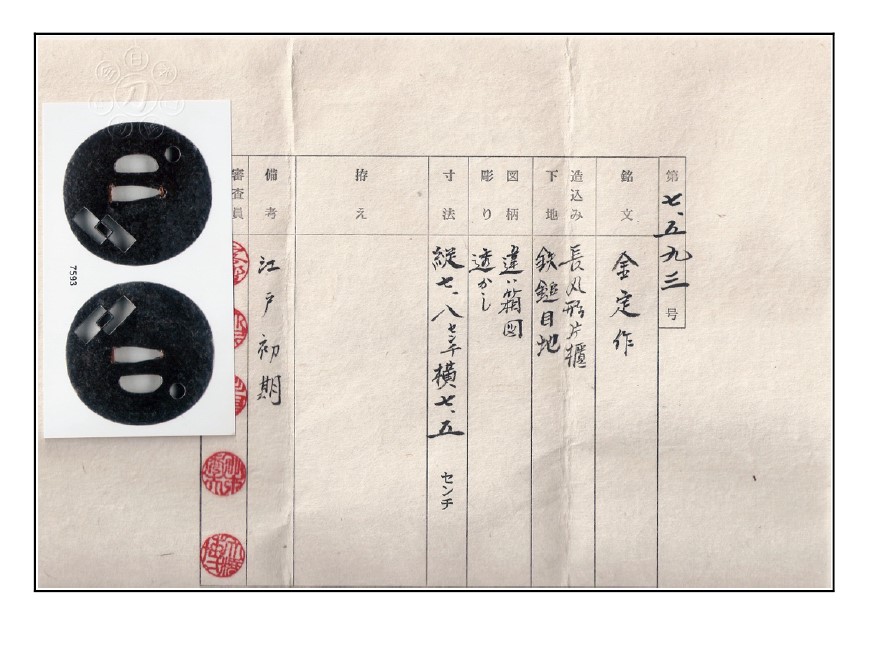

Basic Information

Material: Iron tetsu (鉄)

Age: Early Edo Period, (Edo jidai shōki 江戸時代初期)

Size: 7.5 cm X 7.8 cm, 3.0 mm at rim Signature: Kanesada saku (金定作)

Shape: elongated round, (nagamaru-gata 長丸形) Surface Finish: hammer marks, (tsuchime-ji 槌目地)

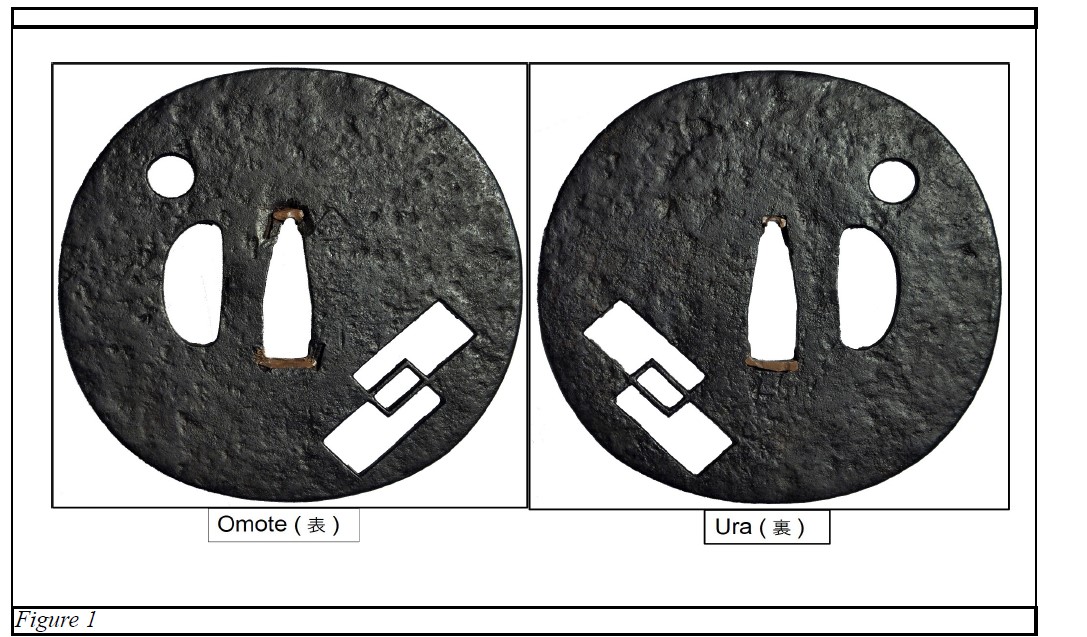

The tsuba (鐔) in Figure 1 displays a wonderful deep rich blackish-brown patina sabi (寂) and a very finely hammered surface (tsuchime-ji 槌 目 地 ) along with a very characteristic surface pattern consisting of fine pinpoints (ji-mon 地紋) found on many old iron tsuba. This complex surface treatment adds greatly to the overall aesthetic sense of the tsuba and emphasizes quiet simplicity, impermanence, and subdued refinement (wabi-sabi 侘び寂び). The design consists of two separate small openwork (ko-sukashi 小 透 ) elements. The large and elongated small accessory knife hole (kozuka hitsu-ana 小 柄 ) is a characteristic of Japanese sword fittings popular from the Azuchi- Momoyama Period to the beginning of the Edo Period.

Analysis of the Design

The first openwork design, in the upper left as you face the front of the tsuba, is the full moon (mangetsu 満月). The second, in the lower right, is of an open letterbox (chigai-bako 違箱).

According to Robert E. Haynes, as relayed via personal communication, these two elements together tell a story from the famous Tale of Genji (Genji monogatari 源氏物語) written by Murasaki Shikibu and published in 1008 CE.1 This early novel the first in all of human history was a popular source of different types of fine art produced at the beginning of the Edo Period.2 The Tale of Genji specifically makes reference to reading love letters by the light of a full moon. This tsuba's openwork design likely illustrates this scene from the novel in negative silhouetted openwork (in-sukashi 陰透).

Discussion

The tsuba is signed simply with three characters (Kanesada saku 金定作) on the front (omote表 ) side. The middle character being a bit harder to read then the first and last character of the signature. A detailed view of the signature can be viewed below.

Kanesada was likely a student or an assistant to Meijin Shodai Kaneie (名人初代金家) and was located in Fushimi (伏見) just outside of the old capital city of Kyōto (京都) in Yamashiro Province (山城國). This was the location of Toyotomi Hideyoshi's grand castle Momoyama-jo (桃山城), which was destroyed in 1600 CE. The signature is in a somewhat different form from what is found in the English reference Signatures of Japanese Sword Fittings Artists by Markus Sesko, page 120.3 The only signature example given includes the location information of Yamashiro Province as well as the honorific title of Fujiwara (藤原). Markus gives the working period for this artist as 1570-1621 CE. A reference to the artist is found also in The Index of Japanese Sword Fittings and Associated Artists by Robert Haynes (ID# H02526.0) which gives the date of the artist's working period to be circa 1600 CE.4 The artist was known to make tsuba of an early sword smith (tōshō 刀匠) or armor smith (katchūshi 甲 冑 師 ) designs. This is quite different from what Meijin Shodai Kaneie normally produced; he often employed soft metal inlays and designs carved in high relief (taka-bori 高彫). The overall design of Kaneie work is reminiscent of the Chinese School of painting first imported into Japan during the T’ang Dynasty (618–907 CE). According to Robert E. Haynes (via personal communication) this artist was active a generation later than Meijin Shodai Kaneie. This would put his active period around the time of the (Keicho 慶長) Era (1596-1615). No records of the birth or death dates remain for this artist; only an approximate working period can be determined. It was said also that the artist forged the iron plates used by Meijin Shodai Kaneie for his tsuba. The first character of this artist name: (kane 金 ) was likely taken from the first character of Kaneie ( 金 家 ). This first character differs from what was used by the many generations of sword smiths using the art name Kanesada (兼定).

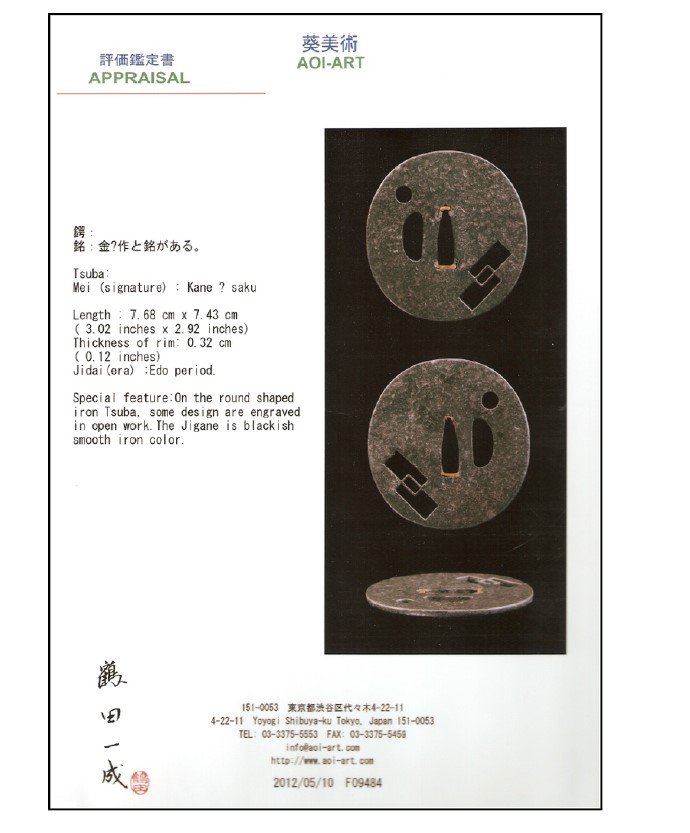

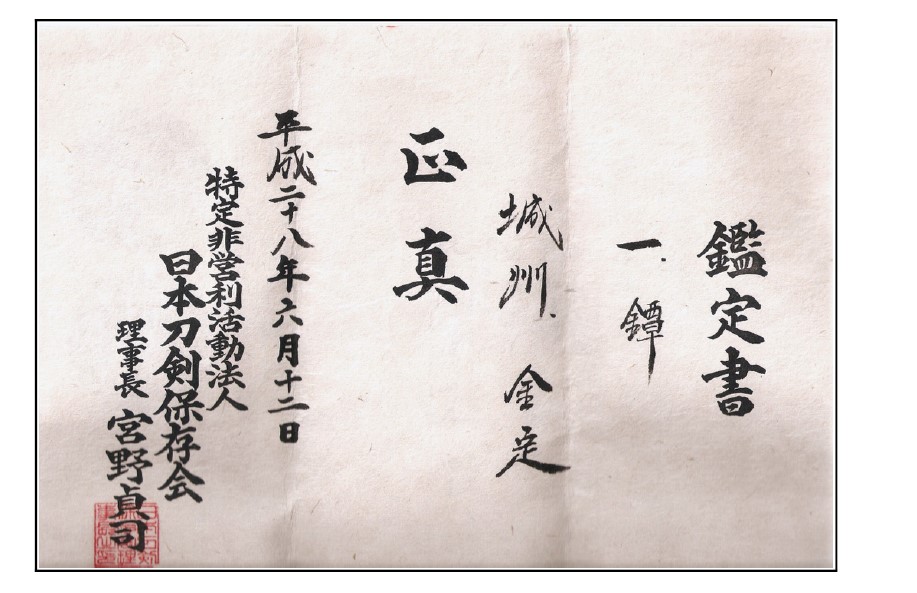

Appraisal Results

In May 10, 2012 this tsuba was issued an Aoi-Art appraisal stating “Kane ? Saku (金?作)” due to the condition which made the signature more then a bit hard to read. The age of the tsuba was listed vaguely as the Edo Period. No details other than size and a comment about the overall shape and color of the patina were provided on the appraisal document.

In February of 2016 the tsuba failed (Nihon Bijutsu Tōken Hozon Kyo-kai 日本美術刀剣保存協会) NBTHK [Society for the Preservation of the Japanese Art Sword] (shinsa 審査) at the Japanese Sword Museum in Tokyo. The explanation given for its failure was that the tsuba has a false signature (gimei 偽銘) of Kaneie (金家).

The tsuba was later submitted to (Nihon Tōken Hozon Kai 日本刀剣保存会) NTHK-NPO [Society for the Preservation of the Japanese Sword (a registered non-profit organization)] shinsa on June 12, 2016. It passed with a direct attribution to the artist Kanesada (金定) of Jōshu Province (城州

) after the area of the signature was lightly cleaned. The tsuba was dated to the beginning of the Edo Period by the NTHK-NPO. The point score at the shinsa was 79 and it was issued a written appraisal (kanteisho 鑑 定 書 ), confirming the tsuba's quality and authenticity. This is equivalent to the (Tokubetsu Hozon Tōsōgu Kanteisho 特別保存刀装具鑑定書) papers issued by the NBTHK at the Japanese Sword Museum in Tokyo. Jōshu is an older but commonly used alias for Yamashiro.

Conclusion

The discussion of this fine and controversial tsuba has been interesting and entertaining. I would like to personally thank Robert E. Haynes for identifying the meaning of the openwork design elements of this tsuba and their connection to a classic work of Japanese literature.

References

Wikipedia Entry: The Tale of Genji, URL: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Tale_of_Genji

Wikipedia Entry: Tawaraya Sōtatsu, URL: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tawaraya_Sōtatsu

Signatures of Japanese Sword Fittings Artists, by Markus Sesko, Copyrighted 2014.

The Index of Japanese Sword Fittings and Associated Artists by Robert E. Haynes, Copyrighted 2001, Nihonto Art Publishers.

Real Life Kantei of swords 15: Is it Japanese ?

F. A. B. Coutinho and W.B. Tanner coutinho@dim.fm.usp.br and tannerwb@gmail.com

Introduction

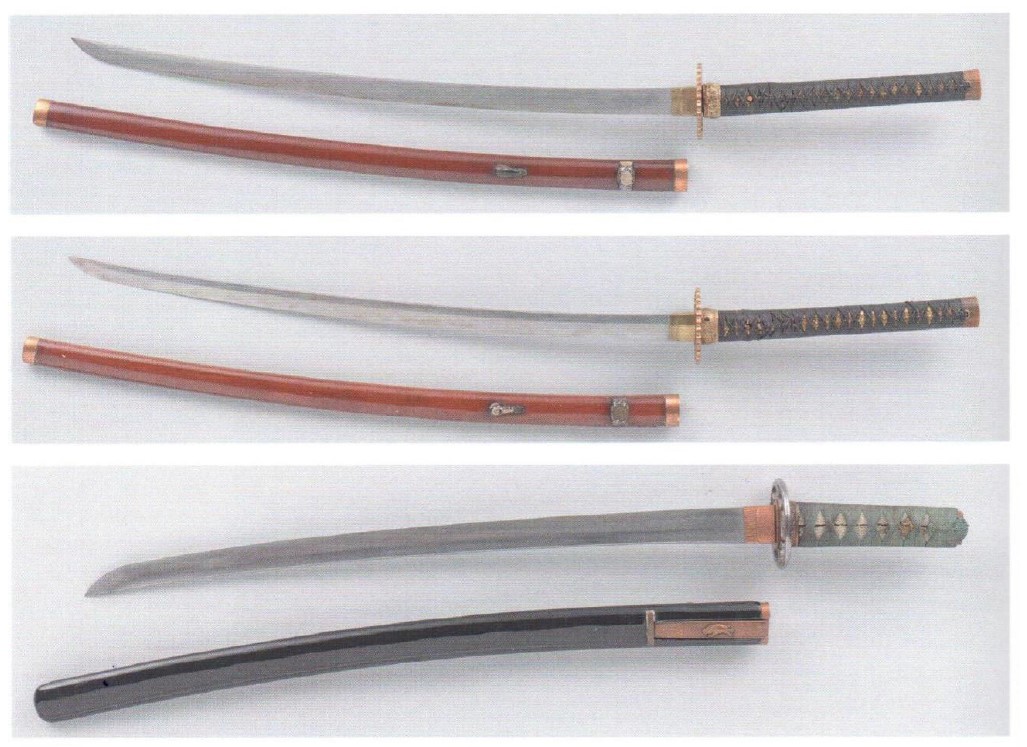

There is a type of sword called a Dha that according to (Greaves n/d ) is a generic term for a sword or knife from one of the various ethnic groups that make up the areas of Burma (Myanmar), Siam (Thailand), Cambodia and Laos. What is peculiar with this kind of sword is the similarities is has to the Japanese samurai sword.

According to (MacNab (2010) page 223) "it has a single curved, single-edged blade similar in shape but not in quality to a Japanese samurai sword." Many other books also acknowledge this similarity.

We recently examined a Dha that appears to have more Japanese influence than other Dha we have seen. This article will focus on this Dha.

The Sword

The sword fully mounted in its scabbard is show in Figure 1

Figure 1- The sword mounted in its scabbard

In Figure 2 we show the blade out of its scabbard . The hilt cannot be removed without heavy work and this is an important fact we will discuss later ( see Appendix).

Figure 2- The sword out of its scabbard . The hilt cannot be removed.

This sword was quickly identified by an oriental arms expert as a Dha. (We shall explain latter how a collector of Japanese swords can identify swords of other parts of the world.) The Dha was used in Burma and Thailand, until quite recently. However, this sword appears to resemble a Japanese Sword more than other Dha we have seen.

This Dha is unusual for a number of reasons.

First, the blade is better than the blades we have seen in other Dha . It appears to be forged and its edged is fire hardened, not like a Japanese hamon but similar in appearance. Although it is not uncommon to find oriental arms (from the Far East) with a hardened edge, we have never seen this level of hardening in other Dha. Also, there are signs of forging and the steel looks to have been subject to more forging work than what is usually found in far eastern swords. On first glance is would be tempting to assume this blade is a long hira zukuri Japanese blade of poor quality.

Second, this sword is mounted with a small habaki and a small tsuba. This is not common in other Dha we have seen. The ones we have seen with habaki, were of 20th century manufacture.

Third, the scabbard of the sword is of niello design. Not quite the niello we find in Caucasian swords but definitely niello. This actually increased our uneasiness about this sword. Why does a Japanese sword , mounted as a Dha, have a scabbard and hilt (see figure 3) in the style of a Caucasian sword?

Figure 3- The hilt of the sword.

The above swords represent typical Dha . These were on sale at Wallis and Wallis recently. Note that the above swords have no Tsuba or Habaki, but the blades resemble (perhaps vaguely) a Hira Zukuri Japanese blade.

Identification of the Sword

This sword is a Dha acquired from Thailand. In fact the Dha is the national weapon of Burma but was used in many neighboring countries. It is probably from the late ninetieth or early twentieth century, but it is very difficult for a Japanese sword collector to identify swords like this. (see Appendix for some hints on how this can be done). It is well known and explained in the book by Richardson (Richardson (2014)), that Thailand was influenced by Japanese warriors in the 16th century, just before Japan was closed to the world by the Shogun. For example, Dha where used in pairs one large and one small, like a katana and wakizashi. The smaller Dha is generally identical to the big one. The Dha is frequently described as being similar to Japanese swords but of low quality. We believe in fact, that the Dha was inspired by the Katana but don't agree that they are entirely similar.

An expert in Oriental Arms that we discussed this with shared the following comments with us. "This looks to be Thai; it belongs to a subgroup of dha from that culture that's deliberately patterned after Japanese swords. Note the visual effect of the hilt deco, consciously imitating the twisted braid cord wrap on a katana or tachi hilt. However, the grip is still of round cross- section, with the flaring bell shaped ferrule, in keeping with the functional norms of Thai swordsmanship. Blade profile is heavily Japanese influenced too, as is the habaki. This is the result of Japanese adventurers going to SE Asia in the 16th , begin 17th cent. to seek employment as mercenaries. There were also Portuguese and Chinese down there doing the same thing. The kings of Siam hired many Japanese, who were put into their own military unit. The practice stopped when Japan closed its borders, and I recall there being some sort of political upheaval in Thailand where the Japanese were accused by the opposition side of being subversive, or traitorous. Still, during their term of service, these Japanese were trusted more than the Chinese or Portuguese -- Japan was far away and not interested in territory in the area, whereas the Ming Dynasty was too close and was pressuring Burma. The Portuguese had valuable firearms technology but were still suspect because their country was actively building an Asian empire, and aggressively converting natives to Christianity" (2017 – Artzi, Oriental- Arms.com)

Japanese Influence in East Asia.

In a book published by the Royal Armories (Richardson (2014)) entitled East Meets West, an article in this book helped us make sense of the Japanese influence in Vietnam [ and in Southeast Asia in general] . This book contains a series of wonderful articles about episodes when Europeans encountered Asians and exchanged gifts, some of which were swords. It is well known that until the 19th century these contacts were infrequent. The article is this titled " A Diplomatic Gift Full of Surprises " and was written by Eveline Sint Nicolaas of the Rijsksmuseumm, Amsterdan. It discusses Japanese swords exported to South East Asia and Japanese swords made there (or made in the style of Japanese swords) in the seventeen century.

The book describes a rack full of oriental arms that belonged to Cornelius Tromp (1629-91). This rack was given to him by a friend, called Wemans, who lived in Batavia (present day Jakarta). Tromp added to the rack quite a few items and among them the three swords shown below in Figure 4. The book describes these swords as follows: “At first glance , the swords appear to be of Japanese manufacture; however, on closer inspection it can be to have various features which are typically Vietnamese, or at least Southeast Asian. The two almost identical [top two swords shown in Figure 4] swords have Vietnamese style tsuba or hilt guards and a type of tusk pommel that is often found in Vietnamese weapons. Finally the band connecting guard and the hilt, know as ferrule, has Vietnamese ornaments, while the way it was mounted, tapered and widening toward the guard is also Vietnamese.” When the swords were dismounted in the 1970s, some of the blade turned out to have a hole in the tang while others did not. Blades made in Southeast Asian typically don't have a hole in the tang while Japanese swords always have a hole on the tang (See Appendix).

In conclusion, the swords seem to have blades that are Japanese in form, yet were probably made in Vietnam or some other part of Southeast Asia. The exception is the sword with green hilt binding, which appears to be an actual Japanese sword. [This is the third sword on the bottom of figure 4.] The other weapons may have been made by Japanese swordsmiths who found themselves in Vietnam and lost touch with their fellow craftsmen in Japan after the Island went into isolation in the 1630s. Successive generations of armoires produced weapons which were basically Japanese in design, yet had all kinds of local, Vietnamese, features.

It is, therefore, very likely the Dha was influenced by the Japanese sword since the 17th century. It seems, however, from the literature we read that contacts between Japan and Thailand (Siam) decreased a lot after the 17 th century, which was to be expected with the closure of Japan during the Tokugawa Era. So one may question why this sword appears to have so much Japanese influence. In our opinion, this sword is not very old, and it seems to have been more influenced by the Japanese sword than other Dha that we have seen. Thailand was allied with Japan during World War II, following numerous pre-war diplomatic exchanges and the beginning of a Japanese invasion of Thailand. A Treaty of alliance was signed between Thailand and Japan on December 21, 1941, and on January 25, 1942 Thailand declared war on

the United States and Great Britain. During the war Japan stationed 150,000 troops on Thai soil.

We think that this Dha was made in this period. Our conclusionis based on the comparison we made of Dha examples found in literature that utilized habaki and tsuba. (As mentioned before, neither habaki nor tsuba are commonly used with Dha). These swords, however, were all dated to the period just before until the end of the WW-2.

Figure 4- Three swords manufactured in Vietnam that show Japanese influence.

The Niello scabbard was a surprise for us. We thought that Niello was found only in weapons made in the Caucasus. However, upon close inspection of the scabbard we realized that this Niello is not the same as the Niello found in the Caucasus. With further research we discovered that Niello was actually invented in Thailand. The reader can find on the Internet many beautiful and old pieces decorated in this fashion. This was a pleasant surprise, because, it is another piece of evidence that this Dha was in fact made in Thailand.

Conclusion

When we saw this sword for the first time we were a bit surprised. The blade appeared to be a long Hira Zukuri Japanese blade, it had a habaki, and the mount has a small tsuba. However, the hilt was glued to the tang and of a form completely different of what we have seen before. Finally the scabbard was of Niello that at that time we thought was only found in swords made in the Caucasus.

After some research we become convinced that the sword was a Thai Dha. It is, however, a different Dha from the ones we have seen before. It shows signs of forging and the edge is fired hardened. As explained before, these features are not common in Dha, however examples do exist. We do not know where this Dha was made. When we consulted a specialist in Dha and reviewed his reply (transcribed above) he was convinced this is a Dha was from Thailand. As mentioned before, the Dha are considered to be strongly influenced by the Japanese sword. We found evidence of this in an article in the book by Richardson( Richardson ( 2014)) that has examples of three swords dating from the seventeen century that clearly show the Japanese influence on the appearance of the Dha.

Finally we learned that Niello was actually invented in Thailand which support the provenance of this sword being from Thailand. Since the Japanese influence over Thailand was not that great we think that this sword was made during the WWII when a large number of Japanese were troops stationed there. This explains why the sword looks new and why it shows so many signs of Japanese influence.

What was originally a mystery became very clear to us. The sword was probably made in Thailand during, or just before the Second World War. The form of the blade was strongly influenced by the appearance of the Japanese sword. So was the decoration of the hilt. The scabbard is atypical example of Thai Niello. The sword is in very good condition and is pleasant to look at, but definitively not Japanese.

APPENDIX

It is extremely difficult to identify where a sword was made if you have not previously seen a correctly identified example. It is easy for westerners to identify a European sword, because we see a lot of them in movies. However, Southeast Asian swords are not commonly used in western movies.

One characteristic that usually helps is to look as how the Tang is attached to the Blade. In a European sword there are steel pins that transfix the hilt the tang and are hammered at the other side of the hilt. There are usually more than two pins so the blade is permanently fixed to the hilt. (One exception are small swords that have the end of the tang transformed into screws and that are fixed by a bob on the top of the hilt) . Swords of the Far East (except Japanese ones) have their tang glued to the hilt. Since the blade we are examining has its tang glued to the blade we can conclude that the blade is from the Far East.

To learn about different swords, one must consult books with titles like “Swords of the World ". The following references are just examples of the these kinds of books: (MacNab (2010) ) , (Cope (1998) ) and Winters ( 2013) . Unfortunately these books may only have one or two examples of the swords from each country. Eventually one needs to choose two or three swords that are similar to the sword being examined and consult the “sword bible” (Stone (1999) ) .

REFERENCES

Richardson (2014) - Thom Richardson ( editor), East Meets West . Diplomatic Gifts of Arms and Armour between Europe and Asia, Royal Armouries , London

MacNab (2010) -Chris MacNab ( Editor), Swords . A Visual History , DK , London

Cope ( 1998) - Anne Cope ( Editor) , Swords and Hilt Weapons, Weidenfeld and Nicolson , London

Oriental-Arms.com (2017) – Artzi email

Stone (1999) - George Cameron Stone, A Glossary of the Construction, Decoration and Use of Arms and Armour in all countries and in all times, Dover, New York

Greaves (nd) -Ian A. Greaves, Mark I. Bowditch & Andrew Y. Winston, The Swords of Continental Southeast Asia

Winters ( 2013) - Harvey J S Winters and Tobias Capwell, The Ultimate Illustrated Guide To Knives, Swords, Daggers & Blades, Lorenz Books, New York

CONNOISSEUR’S NOTEBOOK

James Lancel McElhinney © 2017

崎陽唐人鐔

(KIYOU TOUJIN TSUBA)

A New Classification Denoting Chinese Carvers Working in Nagasaki During the Edo Period

These sword-guards represent a specific, unique, identifiable and unmistakable species of design and workmanship. While these pieces now have been identified as the work of Chinese carvers who emigrated to Nagasaki, identical guards bearing no signatures might still be classified simply as Nanban tsuba. Given the specificity of style, workmanship, etc., continuing to apply such a general heading to these objects would be inappropriate. Instead we might classify these, and unsigned works in this style as Kiyou Toujin Tsuba: 崎陽唐人鐔, (Nagasaki “Chinaman” sword-guard). Kiyou (崎陽) is an archaic name for Nagasaki used by the Chinese community, and by those with close ties to it. For example, when Jakushi I became a monk, he changed his name to Kiyou-Sanjin (崎陽山人) or “Nagasaki Hermit”. During the Edo period, it seems that Chinese people were identified in Japan as Toujin (唐人). The character 唐“Tou”, which may also be read as "Kara". 唐 is the same character as Tang, an archaic term for the Middle Kingdom, derived from the name of an imperial dynasty that ruled China from 618-907. Tang was an ethnic designation for people in South China, whereas Han 漢 applied to northern Chinese. The cantonment in which Nagasaki’s Chinese population resided was known as Toujin-Yashiki 唐人屋敷,a somewhat grandiose term, which could mean “Chinaman palace” or “emporium”. Given the evidence at hand, and the need to dismantle vague terminology like “Nanban”, we many now identify a new "school" within the canon of Japanese sword-guards. For reasons stated above, I propose that such objects henceforth be identified as "Kiyou Toujin Tsuba" 崎陽唐人鐔, (Nagasaki Chinese-maker tsuba).