Real-Life Kantei of swords #18: An intellectual escapade

By F.A. B. Coutinho (coutinho@dim.fm.usp.br)

Real-Life

Kantei of swords #18: An intellectual

escapade

F.A. B. Coutinho

(coutinho@dim.fm.usp.br)

In previous articles, swords of well- known swordsmiths were described. This

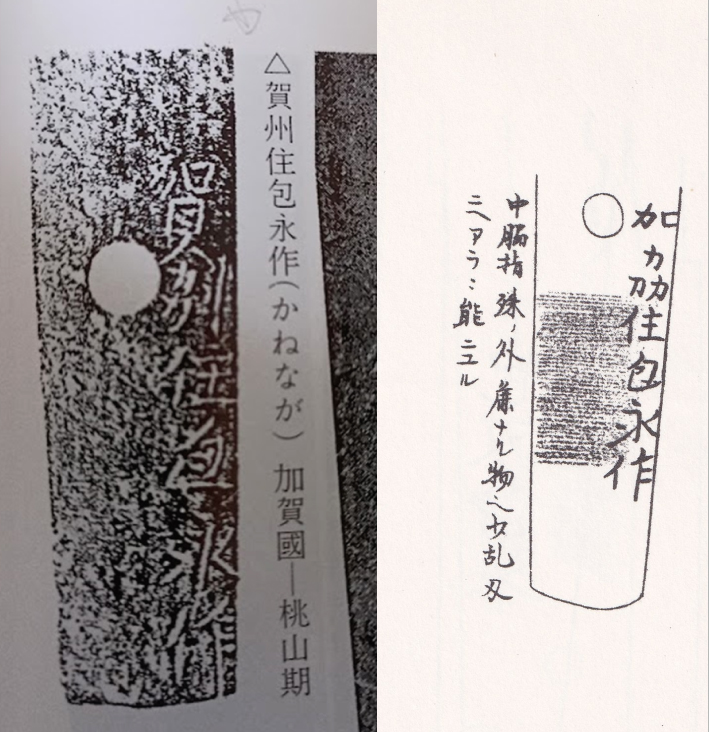

article discusses a katana signed 加州住包永作 a wakizashi signed 加州包永作 .and a yari signed 加州住包永. by what

appears to be an obscure smith called Kashu Kanenaga. Both swords have NBTHK certificates and the wakizashi is well-described by known

experts. The aim is to show the readers how difficult it was some time ago to identify

less well-known smiths and more importantly to understand the certificates. There

is information in the certificates that the curious owner should want to

understand. There are other reasons given below.

Although, this wakizashi’s smith is not well-known, this sword is

interesting for three reasons.

First, the

time of its production appears to be from the 安土桃山時代(

Azuchi–Momoyama period (1573- 1615 )) that is from Eiroku (1558–1570) to the beginning

of Keicho (1596–1615). This

period corresponds to the end of the Sengoku

Jidai when tremendous infantry battles took place. In Japan, as in Europe (DeVries (1966)), battles using only Calvary became very inefficient.

Instead, battles became more strategic, like a game in which three kinds of weaponry

were the primary playing pieces. These were calvary, artillery (with cannons)

and infantry. These types of weaponry were used very strategically, like in a

game of scissors, stone, and paper, but with fewer elements of luck. During this

time many great generals, such as Uesugi Kenshin, Takeda Shingen, Oda

Nobunaga, distinguished themselves and some died in battle. However, infantry

battles were fought by common soldiers, not nobles, who must be properly armed

to be victorious. The sword we will discuss might have been made for these

warriors.

Second, the wakizashi is unusual. It is reminiscent of the Roman Gladius

infantry sword, which was used for close combat or for hacking away at things much

like you would use a machete. It is an atypical blade; very thick, heavy, short

for the era and specially quenched. It looks like a true battle sword.

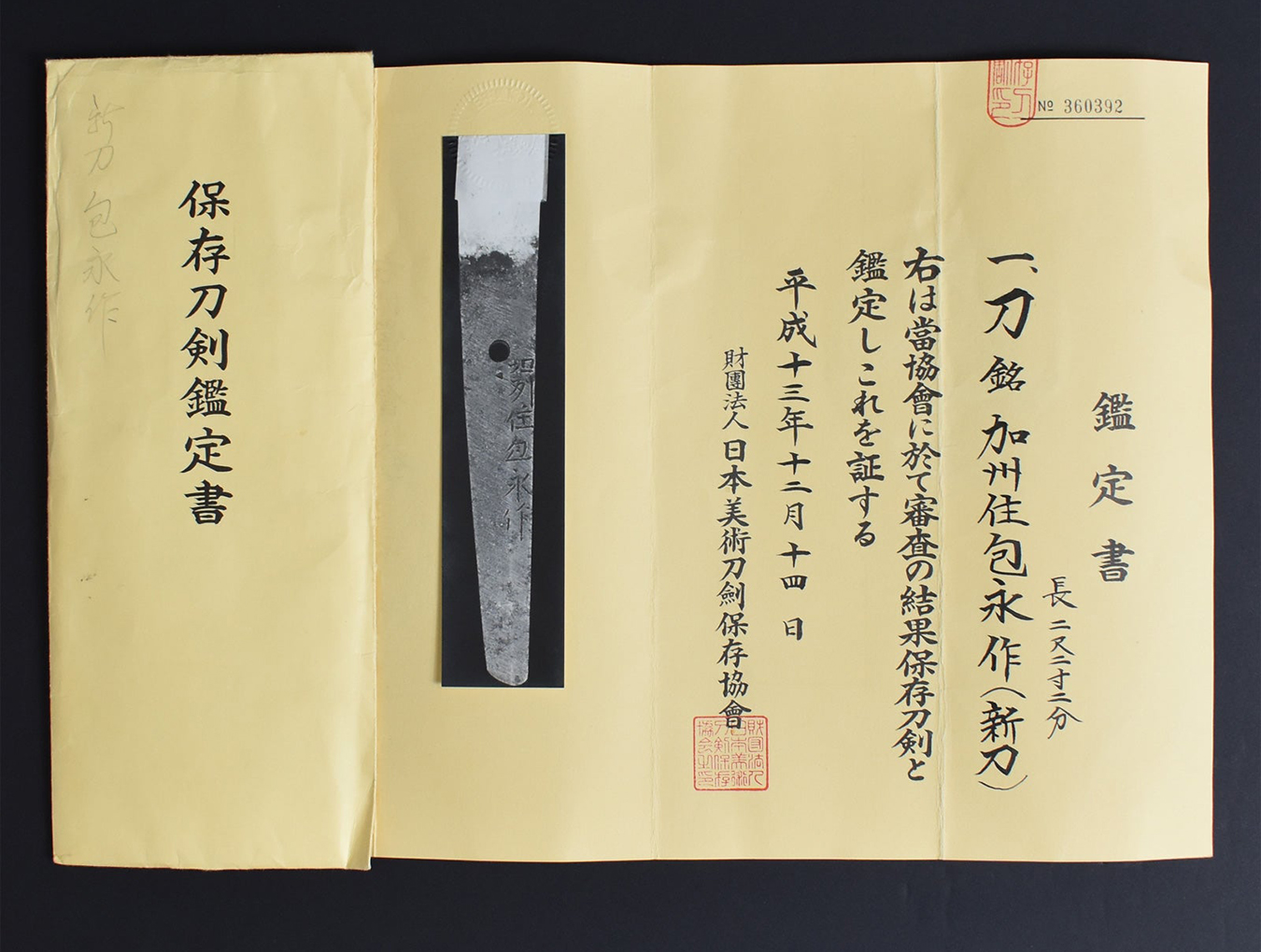

Third, the wakizashi has NBTHK

Hozon certificates attributing it to the

Shinto period. See figure 2 below. Since the blade is signed and certified, as

mentioned before, one would think that nothing more could be added. The

certificate does not say how its conclusion was reached. Perhaps, since the

NBTHK has a huge data bank with oshigata of swords they checked the signatures and identified

the smith.

The NBTHK, places the sword in the

Shinto period which was at the time the paper was issued considered to

begin at the Keicho era. This is no longer the

case for at least one author (Nakahara (2010) page 34)

and we believe the clarification that the sword is Shinto in the certificate was done to distinguish between two possible

generations of Kashu Kanenaga smiths.

However, the existence of two generations

is not guaranteed, so this will be an interesting problem to discuss.

Sword history in the occident

After an exceptionally long and satisfying discussion about its

peculiarities with Yuji Fukuoka of Tokugawa

Art, I purchased the sword. However, I sold it, and it was later re-sold by Grey Doffin (Japanese Sword Books and Tsuba). The description below

includes information from both Grey Doffin and Yuji

Fukuoka as well as my own thoughts.

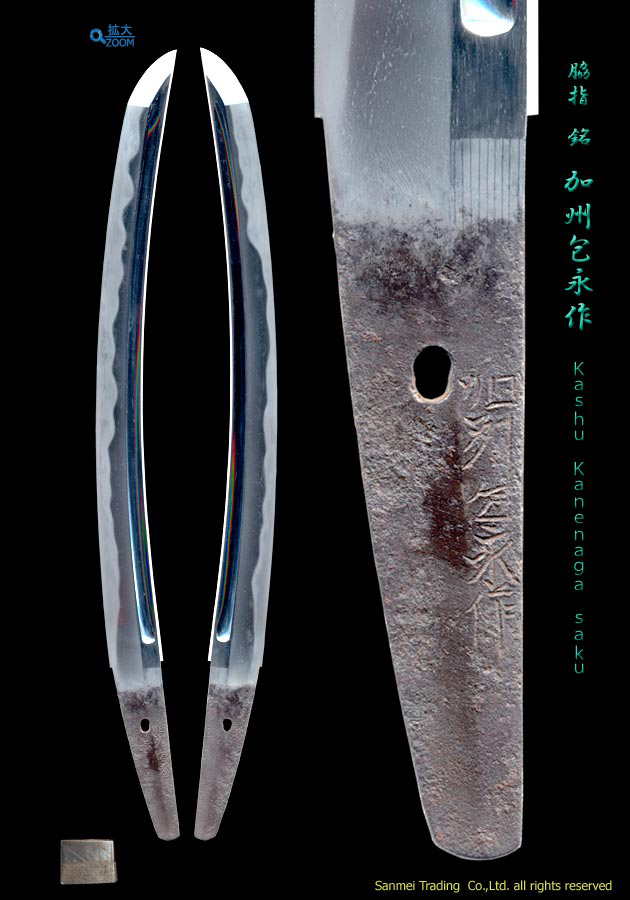

Sword description: The wakizashi

Sugata: Shinogi-zukuri with an iori-mune

and there are rounded end Bo-hi grooves on both sides.

Nagasa = 43.4cm Sori =1.8cm Moto

Haba =37.8mm Saki Haba =28.1mm Moto

Kasane = 6.7mm

The

mihaba of this sword is extremely wide,

it is thick in Kasane and deep in

curvature. While heavy in hand, the blade has a solid construction and a broad

point. It is a heroic wakizashi sword,

fit for close quarters combat and is in “almost” original condition although

made 450 years ago.

Kitae: Kitae-hada is conspicuous Itame-hada

(wooden grain) and mokume (burl marks) mixing

in with the swelling masame hada pattern along cutting edge. Hiraji

is covered in deep and speckled ji-nie that generates reflecting irregular yubashiri effect clearly over the surface.

Hamon: Shows irregular large gunome mixing

in small gunome zigzag and choji-ha

(clove out-line). The quenched edge, also known as the tempered is covered in

thick and vivid nie and deep misty nioi. The hatraki

contains frequent kinsuji (bright

curved threadlike areas) and sunagashi

(streams like blushing area). Tobiyaki spill over surface partially. The entire temper is full in hitatsura, vividly bright and clear.

The temper of the boshi (quenched area

at the tip): is midarekomi

with irregular lines in full temper (hitatsura).

Nakago (tang): ubu

(original) which holds an original clear file-mark kattesagari

slanting left with one mekugi-ana (retaining

hole). The signature in hakiomote is

clearly chiseled, starting with the work of place [Ka Shu] and the smith’s name [Kanenaga] on the shinogi surface.

From the

reference book of [Kozan Oshigata]

1709 (that is Houei 6), Kanenaga was active during the Azuchi-Momoyama period, in the last stage

of

Warring States period, known as Sengoku Jidai. Because of the increased demand

by samurai warriors, the sword shapes became more durable and magnificent. The

subject wakizashi holds an almost

original shape common during the warring states era, the so called Azuchi- Momoyama period before the Tokugawa came to power in 1603.

Its workmanship is not obvious, in the sense that some effort is needed to identify

the details found in this sword. It has majestic

and awe-inspiring power in its shape and girth. Among

similar works of 16th C., this blade is unusual and (for me) a delight.

Below,

is Grey Doffin’s edited description. Grey’s

description of the activities (hataraki)

in the sword is perfect and only remarks and technical notes were added. (not highlighted in this article).

“The hada is fine and tight ko itame

but there are spots (a few) with a hint of slightly coarse grain. The hamon is exuberant gunome

midare with tons of sunagashi

and kinsuji, all covered in ara-ni. There are numerous spots of isolated

temper above the hamon (yo).

There is a marked difference in the width of the yakiba (hardened area) as the hamon progresses

along the blade: in places it is high and in others low, approaching the edge

but never runs off.”

Consider that this sword was specially quenched, so

that this hamon is the result of the last quenching

(not re-tempered). The boshi is quite

complex with ko-maru and a longish kaeri. The boshi covers

the kissaki, almost entirely. The

presence of the hint of coarse grain in the ji

is usually considered by collectors as a small flaw. In fact, as an art sword

this is so, but this sword is an extraordinarily strong battle sword as it totally

fits.

One should note that there are differences between the

descriptions of the hada of the sword

by Yuji Fukuoka and Grey Doffin. Both men are experts

in the appreciation of the Japanese swords. The differences are due to emphasizing

different characteristics of the sword. The

sword is roughly constructed and so difficult to describe. The hada is not homogenous that, in parts it corresponds

to the description by Yuji Fukuoka and in parts to the description by Grey Doffin. The presence of spots of rough grain draws the

attention of Yuji Fukuoka but as mentioned by Grey Doffin

there are parts of fine and tight grain. As mentioned above the quenching of

such a broad sword must have been a complicated process, resulting in a deep sori and inconsistencies in the size and

shape of the hamon.

Figure

1 below, shows a picture of both sides of the sword and in Figure 2 the NBTHK certificate (dated 2010) certificates states that

this sword is Shinto.

The

shape of this sword is unusual. Like the one shown in Figure 7 page 12 of (Martin (2010)), but very wide, much

curved, and somewhat shorter than what is common in the era.

Figure 1- Photograph of both sides of the Blade. This shape is like the

one show in figure 7 page 12 of Martin (2010))

Figure 2- NBTHK Hozon Certificate dated Heisei 22 (2010).

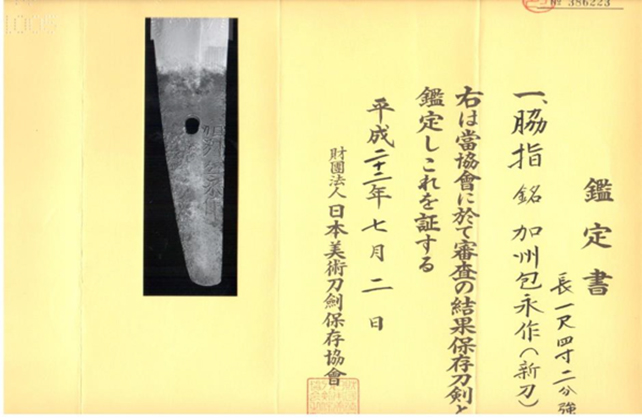

Sword description: The katana

Another sword

by a smith with the same name was sold by Katana Boutique. Figure 3 is a

photograph of the shape and of the nakago of

this sword. The NBTHK attributed it to the same smith’s name and time period (Shinto). The signature includes the kanji

住(Ju) and the carving of the signature is slightly different than our subject

sword. However, the certificate says Kashu Kanenaga in the Shinto

period and so one can assume these are made by the same smith. A copy of the

certificate showing the signature is reproduced below In

Figure 4.

Figure 3- The signature of the same smith on another sword. Note that

there is a 住(JU) and a 作 (SAKU) in this signature.

In Figure 3

above one can see the shape of this katana. The shape shows a tori-zori with

a very shallow saki- zori and narrowing towards the point.

It is typical of the late Muromachi to the beginning Keicho. See for example Paul Martin booklet (Martin

(2010)) where the shape is like the one in Figure 6 on page 6, but

longer. Also, please compare the sword shown in figure 175, page 148 of (Nakahara

(2010)).

Figure 4- The certificate (issued in 2000) of the above sword indicating

that is the work of the smith that worked in the Shinto period.

The

measurements of the katana are as follows: Nagasa =67.3

cm, Sori=1.5 cm, Moto Haba=3.7 cm,

Saki Haba =2.47 cm

Blade description: The Yari

Figure 5 shows a photograph of a Yari.

Note, for future comments, that this signature does not contain the two kanji) 藤原 (FUJI WARA nor the

kanji 作 (SAKU). However, is does use the same kanji for 包(KANE) and 永 (NAGA) Could

this be the smith be our smith?

Figure 5-The signature is like our subject sword. It used the same 包(KANE) and 永(NAGA) but does not include 藤原 (FUJI WARA) or 作(SAKU).

Attempts to Identify this smith in more detail as if we lacked certificates.

What follows is an intellectual effort to understand

the NBTHK attribution.

Some time ago it was very common to find swords for

sale with no certificate and in poor polish. Collectors tried to identify the

smith, and this was done in at least three stages. In this case this is indeed

futile because as shown above the smith who made the wakizashi and the katana were identified by the NBTHK. If there

were no certificates the steps collectors had to follow a long time ago will be

considered.

Step 1-Searching for the signature.

The first step is to search

the smith in books containing list of signatures. In this case this smith is

rarely mentioned in the literature. Some books, mention just one smith with

this name and with the general statement that he worked in the Azuchi- Momoyama period. For example, Tokuno Kazuo (Tokuno

(2004), page 60) mentions only one Kashu Kanenaga in Kaga,

working in Eiroku, and stressing that

his work has sunagashi and that it is wazamono.

But

other books mention two Kashu

Kanenaga one working around Eiroku the other working in Keicho: Marcus Sesko,

(Sesko (2012)), conjectures that the smith

working in Keicho is a second generation of

the one working in Eiroku.

In

three books listed below, the signature of the one working during the Keicho era includes the characters for Fujiwara

but not a Saku, namely the

signature should read, Ka Shu Ju Fujiwara Kanenaga.

Hawley (Hawley (1998) page 124)), however, has the

Fujiwara in this signature but it is optional.

Another point to note is that in the books by Hawley (Hawley (1998) page

124)) in the Meikan

(Honma (POD), and in the book by Shimizu Osamu (Shimizu (1998)

-page 111, for the Shinto smith

and page 110 for the Koto Smith), the Kashu Kanenaga working

in Eiroku includes a 作 (saku) in the signature which is not included

in the signature of the sword smith working in Keicho.

Furthermore, in the books

the signatures of both smiths include a 住(Ju) that is absent in our wakizashi. The books by Hawley (Hawley

(1998), Shimizu (1998) and Honma

(POD) will be referred as the books from now on.

To finish this analysis, the value of the two smiths

in the books mentioned above should be considered and is as follows. In the

book by Hawley the value of the smith working in Eiroku (hence Koto) is the same as the value of the smith

working in Keicho

(hence Shinto) and it is 15 points.

In the book by Shimizu, however, the Koto smith is rated as Ryo (良) that is good, and the Shinto one is rated as Hey (並), that is common. In the book of Tokuno (Tokuno (2004)) the value of the Koto smith (the only cited) is 3.000.000 Yen.

The above leads to the following (false) conclusions.

1) One would be in doubt about the wakizashi.

It does not contain the 住(ju) that is mentioned with respect to both smiths in the books.

2) One would conclude that the katana is by the Eiroku smith

because it contains a 作 (saku) at the end of the signature,

that is the signature is 加州住包永作. On the other hand, one would conclude that the smith

who made the yari is the one who worked around

Keicho

because his signature is

加州住包永 exactly as the books say it should be. But seasoned collectors

would move to step 2 designed to see if the signatures match with the

signatures in the oshigata

books.

Step 2) Examining the signatures.

Without the NBTHK certificates one would compare the

signatures of the pieces. Comparing the

signatures of the wakizashi and the katana the probability that one of them

or both could be fakes should be considered.

The signatures appear to be carved differently but

this might be because the smith used a different tool to carve since the wakizashi is small compared with the

katana. To say that they are from different smiths would imply that one of them

(or both) is (are) unlisted or a fake(s). There are unlisted smiths, that is,

by definition, not listed in the Meikan and that they are probably quite a few but not too

many. The Meikan is a compilation of 23,000

smiths and Hawley claims to have 30,000 smiths. This gives roughly a prevalence

of 800 -1,400 smiths working each year since the year 800 CA. So, despite the

differences, one may assume that they are the same smith. In addition, since neither

is a dated example, one may rely on calligraphic differences and from this

point of view they are the same smith. The signature in the yari, calligraphically, may also be considered by the same smith.

Step 3) Comparing the signatures with known oshigata

This step consists in looking in books that have oshigata (or,

more recently, photographs) of true signatures. This step proved to be very

unsatisfactory. Only two examples were found. The first one is shown in Figure

7a and was taken from the book by Iida

Kazuo (Iida (2011)). The second one is from the old book Kôzan Oshigata

reproduced in Figure 7b This last one

is not an oshigata but a hand copied signature. So, it

should not be used for details.

Figure 7a Figure 7b

Figure 7a) Photograph of an oshigata that appears to be from

our smith because it is from the Momoyama period Figure 7b) Photograph of the signature of

one of the two smiths in the book Kozan Oshigata

Next compare the two oshigata. The two examples appear

to be the same signature, but with minor differences.

Consider the following points.

a) The first kanji Ka in the figure 7a example is the second

kanji Ga of Kaga (加

賀) namely 賀. In the second example it is the first kanji Ka of Kaga namely 加.

b) The kanji 州(shu)

are similar: The

first example uses two chikara characters on the left side [力] top to bottom. The second example

is different because it uses three 力.

c)

On the other hand, both use the kanji 作 (saku) at the end of the signature.

d) The two examples have a 住(ju).

e) Both examples show

the yasurime

as kiri.

Comparing the signatures of the swords with the oshigata in Figure 7a and 7b follows.

a) The two swords and the yari and the oshigata 7b use the same first kanji

for kaga (加), whereas the oshigata 7a uses

the second kanji (賀) for kaga. It should be noted that Shinto Kaga smiths

like Kanewaka

uses the kanji (賀) for kaga.

b)

In both oshigata

the Shû (州)use two chikara characters on the left side [力] top to bottom. In the swords this is

different.

c)

Both the 永(naga) and 作 (saku) kanji are also somewhat different.

d)

The two swords have deep kate sagari yasurime (almost sugikai) while the two oshigata have kattesagari which is more prevalent on kotô works.

d)

In the yari the first kanji (加),) is the first kanj for kaga and the signature does not have the 作(saku) at the

end. It

should be noted that many Shinto

smiths (like Kaga Kanewaka)

of the period did not include 作 (saku) at the end of their signatures.

Concentrating

on the main difference that is in the first kanji,

it does not match the first kanji of

the swords or the yari. Furthermore, the inscription on the side

of the oshigata

in Fig 7a says that the smith is from the Momoyama (which begins in Tensho and goes

to Keicho so it is a very early Shinto. So, we are tempted to say that

both oshigata

are of the Shinto smith and that our

smith is the Koto one. But there is a

discrepancy. The yari has the simple (Ka) Kanji. However, the signature does not

have the saku

at the end. Therefore, the yari might have

been later in the Shinto period.

To

summarize: Naively one might conclude

that the swords are Koto (which is

false), the yari is Shinto and the oshigata are Shinto (which is true). Wrongly this summary does not take into account the fact that the certificates say that

the swords are Shinto. What is needed

is a conclusion that explains every item considered.

One

might also conclude in absence of more information, that the three pieces are Shinto (true) and the oshigata are from the Koto (false) smith despite the annotation (Momoyama) on the side of the oshigata in figure 7a. The two oshigata have in common the kanji for shu

that is more prevalent in the Koto period.

To

summarize: One might conclude that the oshigata

are from the Koto smith and three

pieces are from the Shinto smith (true)

despite of the of the kanji 作 (saku) in the swords

that is absent on the yari.

The existence of the kanji 作 (saku) in the

swords make this conclusion inconsistent with the books. This

explanation also does not agree we all the facts we have.

Since

the conclusions above are contradictory, we are forced to do what we should do

in the first place, that is, to examine the swords and abandon for now the hope

of identifying the smiths by the signatures. This is extra information that we hope

may explain all the information we have.

Step 4)

Examining in more detail the shapes of the swords and of the yari.

There are two measurable properties that

need to be considered. The width of Japanese

swords diminishes as we go from the base to the point. This is a very important

point in kantei.

We can calculate a number to characterize this change. It is given by the

difference between the width of moto haba and the width of the saki haba divided by the width of the moto haba.

This number is called funbari in some auction catalogues Christies's(1992). We shall use this name although, technically, funbari is a different thing (Robson (2005)).

The second number will be used to characterize the curvature of the

sword. It is given by the nagasa divided by

the sori. One can call this number

curvature.

For the wakizashi the funbari is 26% and the curvature is 4

%

For the katana the funbari is 33% and the curvature is 3.7%

Short stocky wakizashi like the Kanenaga

are typical of late Muromachi

and early Keichô shaped blades. They are rare, not

elegant and are usually called Bukotsu. Shinogi-zukuri wakizashi are not as plentiful during Eiroku as hira-zukuri ko-wakizashi (one

shaku, one or two sun). Eiroku shinogi-zukuri

wakizashi tend to be narrower and

longer (one shaku, five sun or so).

However, it can be considered an exotic late Muromachi or early Keicho. Let's compare the funbari and curvature of the wakizashi

with the same measures for a typical late Muromachi or early Keicho shape. The

wakizashi has a curvature of 4% and a

funbari of 26%. The first example is a sword by

Bushu Terushige

dated Bunroku (1595). It has a Nagasa 1 shaku, 9 sun

5 bu and 5 rin.

This can be better described as 1.955 Shaku.

Its Sori is 6 bu and 5 rin or 0.065 shaku. So, its curvature is C=3.3%. The

funbari can

be estimated and is 16.7%. The second example is a

sword by Bishu Mihara Masachika dated Tensho (1573–1592). It has a nagasa

of 1.91 shaku and a sori of 0.04 shaku. So. its curvature is C=2,0% and its funbari can be estimated to be 35.59%. Yet another example is a sword by Uda Kunimune,

dated Tensho

with a nagasa

of 48.2 cm and a sori of 1.22 cm. Hence its curvature is 2.5% and an estimated funbari of 30.76%.

Finally, a fourth example is a sword by Yoshisuke saku dated Bunroku (文禄) (1592). Its nagasa is 28.8 cm and its sori

is 0.82cm. So, its curvature is C=2.84%. Its funbari can be estimated and is 21.1%

The above numbers can be

considered exaggerated with respect to the numbers of a wakizashi by Tamba Kami Yoshi Michi working in the Keicho era from

1595 to 1600. This sword has a funbari of 12% and a

curvature of 2.7%. It also does not compare well with a sword by Kunihiro (Keicho) with a Nagasa of 49.1 cm and a sori

of 1.3 cm that has a curvature C=2.5% and a funbari of 19%.

Thus, our sword compares

better with very late Muromachi

or early Keicho

although is not entirely typical. As mentioned above swords of this type are

called bukotsu and are considered inelegant. This

sword is very unusual and so it is to be expected that it does not compare well

with more typical examples. It is very difficult to find these bukotsu swords

in the literature. Moreover, it is very difficult to find shinogi zukuri wakizashi in the Eiroku era. So, it is not possible to carry out a

statistical analysis of the shape to decide if our sword is Eiroku or Shinto. What can be said

is that our sword is not a typical Keicho wakizashi, that has also usually a bigger kissaki. One

can conclude that the wakizashi is very late Koto and of a special type. A fighting sword,

not an art sword.

The katana is also not a typical Keicho sword, that looks a like suriage Nambokucho swords.

Our katana has a shallow tori zori, which

can be considered typical of Keicho era, but its haba narrows when we go from the base to the kissaki which is small and hence not a typical Keicho sword. In fact,

the funbari

is 33% and its curvature is 3.7%. let's

compare this with a sword by Yasutsugu (Shodai),

signed Higo

Daijo Fujiwara Shimosaka

and the NBTHK 33 Juyo Token. It is a very early Keicho sword with nagasa is 74.55 cm

and sori is 1.82 cm moto haba 3.0cm and

saki haba

2.1cm. So, the funbari is 30% and the curvature is 2.4%. Its kissaki

is not big. Another early Keicho sword by Kunihiro has a nagasa

of 71.6 cm and a sori of 1.2 cm. The moto haba

is 3.2 cm and the saki haba

is 2.6 cm. So, the funbari of this sword is

18.7% and its curvature is 2.23%. The kissaki

of this sword is big, typical Keicho.

So, from the shape one can argue that both the katana and the wakizashi were

made between the late Tensho

era and early Keicho

era but not too late. It is easy to find katana from the Eiroku

period and they do not compare well with our katana.

The yari

has a Shinto shape and was prevalent

in the early Edo era. The yari is the newest piece among the three

pieces and can be little doubt that is Shinto.

Consider all the information

Assume that the three pieces were made by the same

person but at different times. One can do this because

stylistically the signature on the katana

and on the wakizashi are the

same. The signature in the yari is also stylistic the same as the signature of the two

swords.

1)-The wakizashi

was probably made lately during the Tensho era that is in the Momoyama period at the end of the Koto

era.

2) The katana was probably made in the early Keicho era and

the yari a bit later. This shape of yari was very prevalent in the early Shinto period.

Conclusion:

This agrees we the shapes of the pieces and the wakizashi although very unusual is called bukotsu and made for combat.

3) The Kozan oshigata was copied from a piece made in

the Keicho

era but later than our katana. The side inscription of the Kôzan's oshigata notes

that it is a medium sized wakizashi with

a midare-ba hamon (it

looks to be hira-zukuri). This explains the kiri yasurime and

the use of the simplified first kanji for Kaga.

4) The oshigata in

the book by Iida Kazuo was taken from a piece later than the study pieces and made

near the end of the Keicho era or immediately after. This explains

the use of the complete Ka first kanji which

we found on swords by the early Shinto Kaga smith Kanewaka, but still in the Momoyama period. (Tensho to Keicho). Kanewaka also used kiri or kate sagari yasurime.

Conclusion: The

hypothesis 3) and 4) explains why the oshigata are different.

5) The information in the books can be understood as

follows. The signature in the katana

and on the wakizashi were made from Tensho to the beginning of Keicho, that is at the beginning of his career. This explains the use of

the saku in the two pieces and its absence in

the yari.

The absence of

the kanji 住(ju) in the wakizashi can be overlooked

considering how different this sword is. It is unique in our experience and perhaps

an experimental design. Conclusion: The above

explains the information in the books about the signature of the two smiths.

The books list the most prevalent signatures. We have pieces outside the range

that can be considered more prevalent.

6) Finally, one

can understand the NBTHK attribution. The smith worked at the very end of the Koto period and begin of the Shinto period, but surely not during the

Eiroku era and so he is not the Koto smith. Accordingly, the NBTHK had

to say that the pieces are Shinto to make it clear that this smith was

the less valuable one, that is the one working in the Shinto period.

Conclusion:

This explains the NBTHK attribution. As is well known the certificates do not

explain the reasons for the attributions.

This is perhaps inevitable and desirable for several reasons, but it

sure looks like “it is so because we said so”.

Overall Conclusion

The NBTHK is correct. Did they have more information

than the author? An oshigata

of the smith working in Eiroku

with a good description of the work or even better a dated specimen would

clarify the whole issue.

Without that definitive information one can only

conclude that our smith is just a common one who experimented by making an

interesting wakizashi and that was good

for close combat.

Acknowledgments: Thanks to Gordon Robson for reading an early version

of this paper and for sending me the two oshigata. Thanks to Brent Tanner

for some revisions of an early version of this paper and for suggesting the

title. Thanks to Barry Hennick for editing the paper extensively. All mistakes

in this paper are solely my responsibility.

References

1) DeVries (2006)- Kelly DeVries,

Infantry Warfare in the early fourteen century, Boydell & Brewer

LTD, Rochester, NY

2) Nakahara (2010)- Nobuo Nakahara, Facts and Fundamentals of Japanese Swords. A Collector’s

Guide, Kodansha International, Tokyo.

3) Tokuno (2004)- Tokuno

Kazuo, To Ko Tai Kan.

4) Sesku (2002)- Marcus Sesko, Index of Japanese Swordsmiths A-M, page 195

5)Martin (2010)- Paul Martin, The Japanese sword. Guide to Nyusatsu

Kantei.

6) Haley (1998)- W. H. Hawley, Hawley’s Japanese Swordsmith, Panchita

Seyssel-Hawley page 124.

7) Honma (POD)-Honma Kuzan

and Ishii Masakuni, Nihonto

Meikan, Yuzankaku,

Tokyo.

8)-Shimizu (1998)- Shimizu Ozamu, Tosho Zenshu,Bijutsu-Club,

Tokyo

9)- Iida (2011) - Iida Kazuo. Tômei Sôran,

Tokyo

10)- Robson (2005)- Gordon Robson, Glossary of Japanese Sword terms, Japanese Sword Society of the

USA, Inc.

11)- Christies's (1992)- The Compton Collection Sale, New York